- Quantitative imaging biomarkers (QIBs) derived from multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) and radiomics offer superior treatment assessment for bladder cancer compared to RECIST criteria.

- Artificial intelligence (AI) enhances the accuracy of mpMRI-based segmentation and radiomics feature extraction, enabling more precise predictive modeling by integrating imaging biomarkers with clinical data.

- To ensure clinical applicability, multicenter studies with standardized protocols are essential for validating radiomics and QIBs, emphasizing the need for consistent and reproducible AI applications in clinical practice.

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BCa) is the 10th most common and 13th most lethal malignancy worldwide, with urothelial carcinoma as the predominant histology.1 Distinguishing between non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is essential, given their distinct prognoses and treatment approaches. MRI has emerged as a crucial imaging modality for local staging, with the Vesical Imaging Reporting and Data System (VI-RADS) standardizing preoperative muscle invasion assessment.2,3 However, post-treatment evaluation remains challenging due to anatomical alterations.

Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI), incorporating diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI, provides quantitative imaging biomarkers (QIBs) for assessing tumor physiology and treatment response.4 Radiomics, which extracts high-dimensional quantitative features from imaging data, combined with artificial intelligence (AI)-based analysis, enhances response evaluation by detecting therapy-induced changes earlier than traditional Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST).5 This review article explores the role of QIBs, radiomics, and AI in BCa management, with a focus on treatment response monitoring.5

Current Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies

BCa diagnosis typically involves ultrasound (US), cystoscopy, and computed tomography (CT) urography. MRI offers superior local staging and response monitoring, with VI-RADS demonstrating high diagnostic accuracy.6 However, post-treatment assessment remains complex due to treatment-induced muscle layer alterations.

NMIBC is primarily managed with transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURB) with or without intravesical therapy. High-risk NMIBC often requires Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy or systemic chemotherapy. MIBC is traditionally treated with radical cystectomy (RC) with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). However, bladder-sparing multimodal therapy (TURB + chemotherapy + radiotherapy) is gaining popularity, particularly for elderly or comorbid patients. Therefore, there is a growing need for treatment response assessment not only for NAC but also for bladder-preserving multimodal therapy. Furthermore, as immune checkpoint inhibitors show promise as part of multimodal therapy, the importance of MRI-based treatment response assessment is expected to increase further.

Next-Generation Imaging for Treatment Response

QIBs Derived from mpMRI

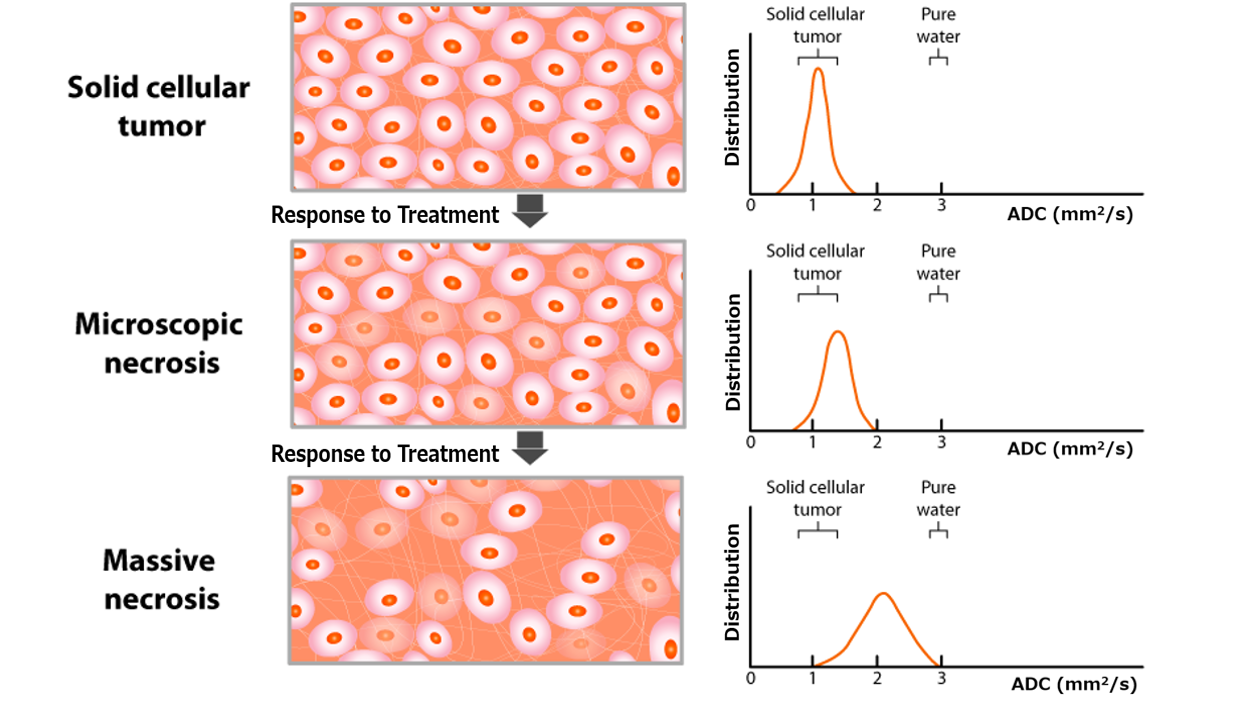

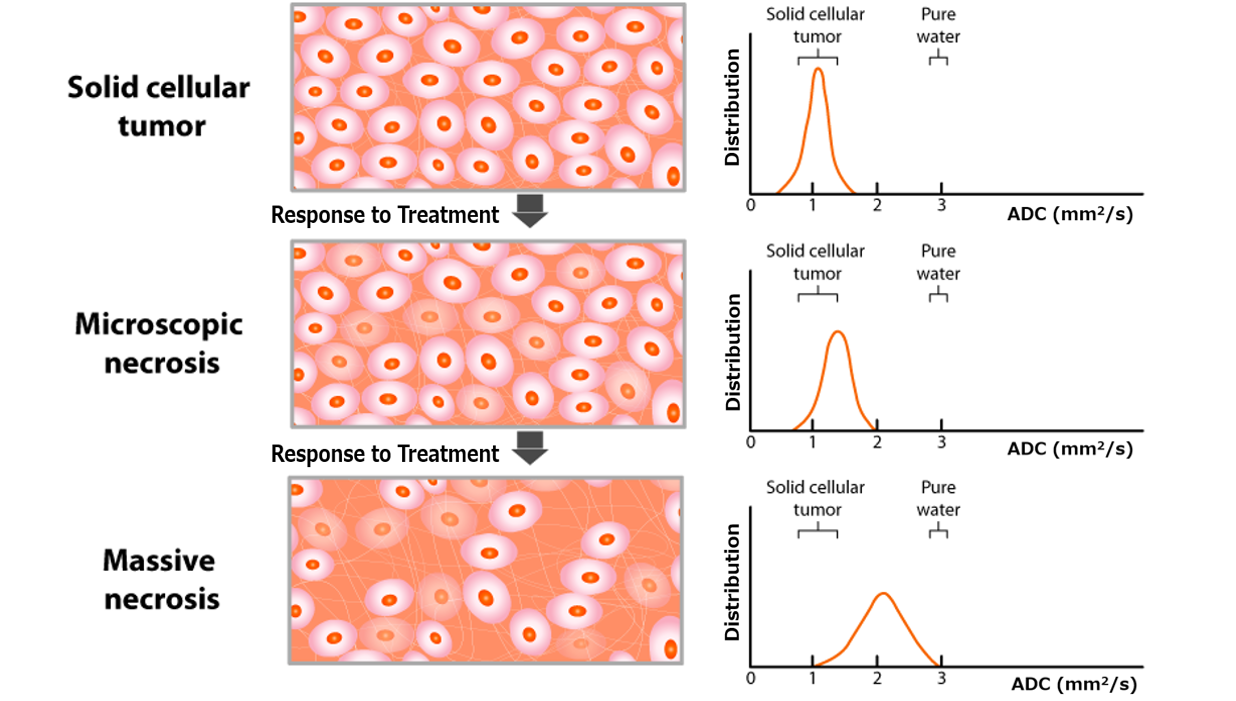

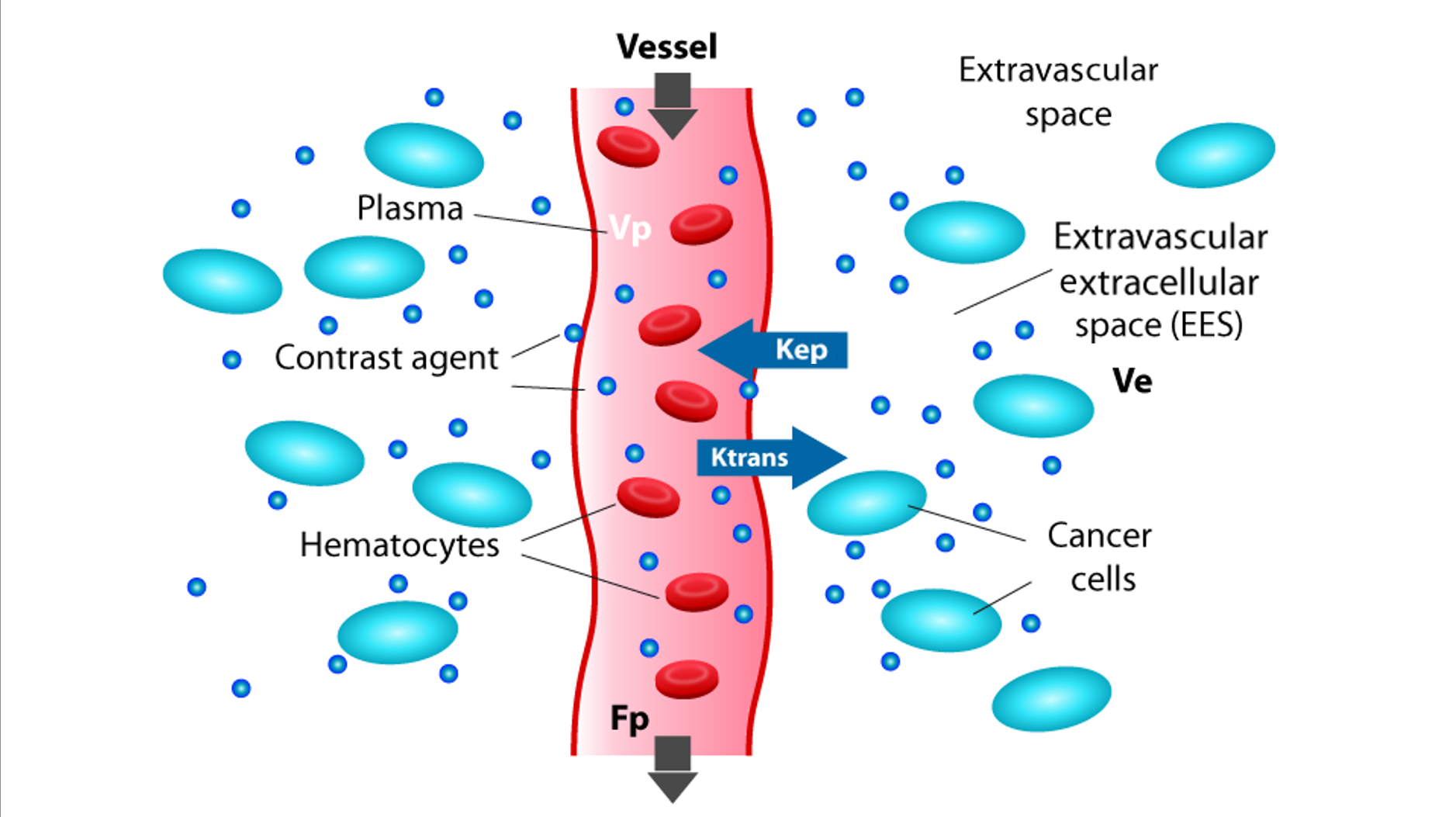

DWI provides apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, which correlate inversely with tumor cellularity. The diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) model further quantifies non-Gaussian water diffusion, and may potentially aid in differentiating healthy from tumor tissues.7 DCE-MRI assesses tumor perfusion and vascular permeability, with key parameters such as Ktrans (volume transfer constant) that may aid in response prediction.5 (Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1. Schematic representation of histologic and corresponding ADC changes during treatment. The ADC map, derived from DW-MRI using at least two b-values, reflects the diffusivity of water molecules in tissues. Water diffusion is restricted by barriers like intact cell membranes, as a result of which ADC values inversely correlate with tumor cellularity. Abbreviations: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DW, diffusion-weighted.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of a vessel, extravascular space, components in these spaces, and the DCE-MRI metrics that can be extracted. DCE-MRI signal intensity time courses can be analyzed using semiquantitative and quantitative methods. Semiquantitative parameters include signal enhancement, wash-in, and wash-out rates. Quantitative analysis models the contrast agent concentration curve to estimate the volume transfer constant (Ktrans), reflecting vascular perfusion and permeability. Abbreviations: DCE, dynamic-contrast-enhanced; EES, extravascular extracellular space; Fp, plasma flow; Kep, rate constant from EES to plasma; Ktrans, volume transfer constant from plasma to EES; Ve, EES volume; Vp, plasma volume.

Radiomics and AI

Radiomics enables early response evaluation by extracting imaging-derived features, including tumor shape, texture, and intensity metrics. Delta-radiomics, which evaluates longitudinal changes in radiomic features, may outperform RECIST in detecting therapy-induced tumor changes.8,9 AI facilitates automated segmentation and feature extraction, and deep learning-based predictive modeling may integrate mpMRI biomarkers with clinical parameters for personalized treatment.

Pretreatment Prognosis Prediction

Prediction by mpMRI

ADC values before BCG therapy in NMIBC, have been linked to recurrence and progression risk.10 Lower ADC values (<1.09 × 10⁻³ mm²/s) have been reported to correlate with worse outcomes in T1 high-grade NMIBC.11 For NAC in MIBC, higher pretreatment ADC values have been associated with better response, with a reported threshold of 1.33 × 10⁻³ mm²/s achieving an AUC of 0.88 for responders.12

Prediction by Radiomics

Radiomics-based machine learning models combining T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), DWI, and ADC have demonstrated high accuracy (AUC of 0.967) in predicting NAC response in MIBC.13 Textural features such as gray level run length matrix (GLRLM) entropy and gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) correlation have been reported to be predictive of response to chemoradiotherapy (CRT).14

Treatment Response Assessment after NAC

Characterization by mpMRI

Post-NAC ADC increases in responders, reflecting decreased cellularity and increased diffusivity. An ADC cutoff >1.65 × 10⁻³ mm²/s reportedly achieved an AUC of 0.74 for differentiating responders from nonresponders.15 DCE-MRI-based washout rates may also distinguish residual visible tumors, with rSI80s (relative signal intensity at 80s) demonstrating high accuracy (AUC of 0.88-0.89).16

Post-Treatment Prognosis Prediction

Immunotherapy & Radiotherapy (RT)

mpMRI-based assessment after pembrolizumab therapy demonstrated moderate interobserver agreement (κ = 0.5-0.76), supporting its role in response prediction.17 DW-MRI-derived ADC changes post-RT correlated with tumor necrosis, with ∆ADC >0.16 × 10⁻³ mm²/s reportedly yielding an AUC of 0.97.18 (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Trimodality Therapy Responder: A 74-Year-Old Woman with Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. A 74-year-old woman with a 53-mm urothelial carcinoma in the anterior bladder wall underwent trimodality therapy. Pre-therapy MRI revealed a lobulated tumor with partial muscle layer disruption on T2WI (a) [VI-RADS 4], high signal intensity on DW-MRI suggesting muscle infiltration (b) [VI-RADS 4], and homogeneous low signal intensity on the ADC map with a mean ADC of 1.160 × 10⁻³ mm²/s (c). Following transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURB), two courses of cisplatin, and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT 60 Gy/30 fr), post-therapy MRI showed significant tumor reduction with no detectable lesions on T2WI (d), DW-MRI (e), or the ADC map (f). The tumor (white arrow) and disruptions/infiltrations (white arrowhead) are indicated. Abbreviations: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DW-MRI, diffusion-weighted MRI; fr, fractions; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; TURB, transurethral resection of the bladder; VI-RADS, vesical imaging-reporting, and data system.

Radiomics-Based Post-Treatment Assessment

Currently, no validated radiomics models exist for post-treatment BCa assessment, presenting an opportunity for future AI-driven studies integrating radiomics with longitudinal imaging data.

Application of AI in mpMRI and Radiomics

Segmentation and Feature Extraction

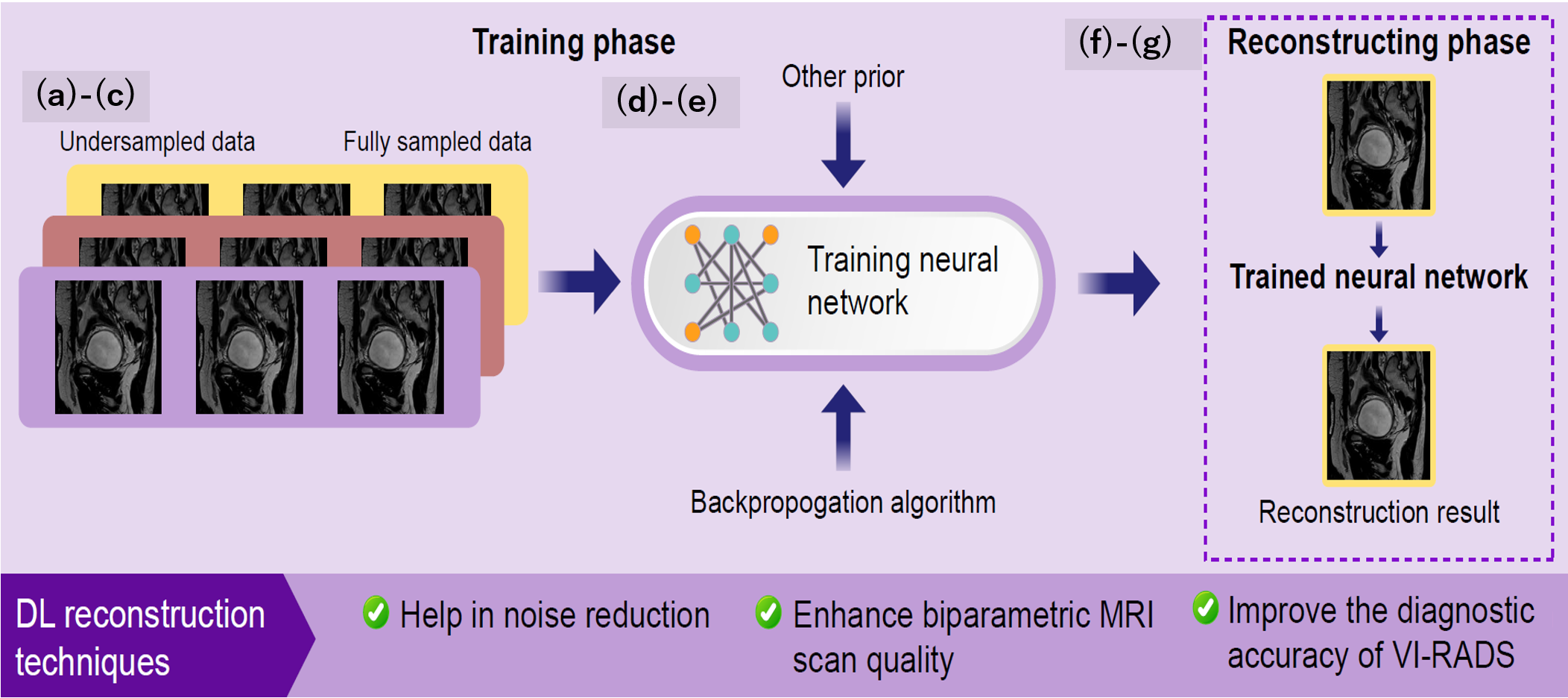

AI enables automated bladder tumor segmentation, improving radiomics reproducibility.19 A deep learning-based U-Net model achieved Dice similarity coefficients of 0.83 (training) and 0.79 (validation) for bladder cancer segmentation.20 (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Deep Learning-Based Segmentation and Radiomics Feature Extraction. Deep learning-based segmentation to automatically identify and delineate regions of interest in medical images, improving precision and efficiency. Radiomics feature extraction then converts these images into high-dimensional data, enabling tumor characterization, disease outcome prediction, and personalized treatment planning. Abbreviations: VOI: Volume of Interest.

Accelerating Image Acquisition

Deep learning-based denoising reduces MRI scan times while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. Studies suggest AI-assisted image reconstruction enhances VI-RADS accuracy.21

Reducing or Eliminating Contrast Agent Use

Generative AI models can synthesize contrast-enhanced images from non-contrast sequences, potentially reducing reliance on gadolinium-based contrast agents.22

Challenges in QIBs and Radiomics

Standardization Issues

Variability in MRI acquisition protocols affects QIB reproducibility. The Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA) advocates for phantom studies and test-retest analyses to enhance consistency.23

Radiomics Reproducibility & METRICS Score

Lack of standardized feature extraction protocols contributes to inter-study variability. The METhodological RadiomICs Score (METRICS) provides a structured quality assessment framework, ensuring radiomics reproducibility and clinical translatability.24

Conclusion

QIBs, radiomics, and AI hold significant promise for BCa treatment response assessment. AI-driven mpMRI analysis facilitates early therapy adaptation and personalized management. However, widespread clinical application requires standardized imaging protocols, multicenter validation, and adherence to rigorous methodological frameworks such as METRICS and QIBA guidelines. Future research should prioritize AI-enhanced response evaluation and the development of validated radiomics models for treatment response assessment.

Written by: Yuki Arita,1 Thomas C Kwee,2 Oguz Akin,3 Keisuke Shigeta,4,5 Ramesh Paudyal,6 Christian Roest,2 Ryo Ueda,7 Alfonso Lema-Dopico,6 Sunny Nalavenkata,8 Lisa Ruby,3 Noam Nissan,3 Hiromi Edo,9 Soichiro Yoshida,10 Amita Shukla-Dave,3,6 Lawrence H Schwartz,3

- Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

- Department of Radiology, Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

- Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

- Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

- Department of Urology, Keio University School of Medicine, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

- Department of Medical Physics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

- Office of Radiation Technology, Keio University Hospital, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

- Department of Surgery, Urology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

- Department of Radiology, National Defense Medical College, Tokorozawa, Saitama, Japan.

- Department of Urology, Institute of Science Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

References:

- Jubber I, Ong S, Bukavina L, Black PC, Compérat E, Kamat AM, et al. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. Eur Urol. 2023;84(2):176-90.

- Panebianco V, Narumi Y, Altun E, Bochner BH, Efstathiou JA, Hafeez S, et al. Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Bladder Cancer: Development of VI-RADS (Vesical Imaging-Reporting And Data System). Eur Urol. 2018;74(3):294-306.

- Arita Y, Yoshida S, Shigeta K, Kwee TC, Edo H, Okawara N, et al. Diagnostic Value of the Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System in Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma with Variant Histology. Eur Urol Oncol. 2023;6(1):99-102.

- Del Giudice F, Flammia RS, Pecoraro M, Moschini M, D’Andrea D, Messina E, et al. The accuracy of Vesical Imaging-Reporting and Data System (VI-RADS): an updated comprehensive multi-institutional, multi-readers systematic review and meta-analysis from diagnostic evidence into future clinical recommendations. World J Urol. 2022;40(7):1617-28.

- Arita Y, Kwee TC, Akin O, Shigeta K, Paudyal R, Roest C, et al. Multiparametric MRI and artificial intelligence in predicting and monitoring treatment response in bladder cancer. Insights Imaging. 2025;16(1):7.

- Jazayeri SB, Dehghanbanadaki H, Hosseini M, Taghipour P, Bazargani S, Thomas D, et al. Inter-reader reliability of the vesical imaging-reporting and data system (VI-RADS) for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47(12):4173-85.

- Bera K, Velcheti V, Madabhushi A. Novel Quantitative Imaging for Predicting Response to Therapy: Techniques and Clinical Applications. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38(38):1008-18.

- Tan WS, Sarpong R, Khetrapal P, Rodney S, Mostafid H, Cresswell J, et al. Can Renal and Bladder Ultrasound Replace Computerized Tomography Urogram in Patients Investigated for Microscopic Hematuria? J Urol. 2018;200(5):973-80.

- Sadow CA, Silverman SG, O’Leary MP, Signorovitch JE. Bladder cancer detection with CT urography in an Academic Medical Center. Radiology. 2008;249(1):195-202.

- de Haas RJ, Steyvers MJ, Fütterer JJ. Multiparametric MRI of the bladder: ready for clinical routine? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(6):1187-95.

- Panebianco V, Barchetti F, de Haas RJ, Pearson RA, Kennish SJ, Giannarini G, et al. Improving Staging in Bladder Cancer: The Increasing Role of Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2(2):113-21.

- Hilton S, Jones LP. Recent advances in imaging cancer of the kidney and urinary tract. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23(4):863-910.

- Kufukihara R, Kikuchi E, Shigeta K, Ogihara K, Arita Y, Akita H, et al. Diagnostic performance of the vesical imaging-reporting and data system for detecting muscle-invasive bladder cancer in real clinical settings: Comparison with diagnostic cystoscopy. Urol Oncol. 2022;40(2):61.e1-.e8.

- Liu IJ, Lai YH, Espiritu JI, Segall GM, Srinivas S, Nino-Murcia M, et al. Evaluation of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in metastatic transitional cell carcinoma with and without prior chemotherapy. Urol Int. 2006;77(1):69-75.

- Compérat E, Oszwald A, Wasinger G, Hansel DE, Montironi R, van der Kwast T, et al. Updated pathology reporting standards for bladder cancer: biopsies, transurethral resections and radical cystectomies. World J Urol. 2022;40(4):915-27.

- Babjuk M, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Compérat EM, Dominguez Escrig JL, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in Situ). Eur Urol. 2022;81(1):75-94.

- Krajewski W, Aumatell J, Subiela JD, Nowak Ł, Tukiendorf A, Moschini M, et al. Accuracy of the CUETO, EORTC 2016 and EAU 2021 scoring models and risk stratification tables to predict outcomes in high-grade non-muscle-invasive urothelial bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2022;40(11):491.e11-.e19.

- Contieri R, Hensley PJ, Tan WS, Grajales V, Bree K, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, et al. Oncological Outcomes for Patients with European Association of Urology Very High-risk Non-muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer Treated with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin or Early Radical Cystectomy. Eur Urol Oncol. 2023;6(6):590-6.

- Balasubramanian A, Gunjur A, Weickhardt A, Papa N, Bolton D, Lawrentschuk N, et al. Adjuvant therapies for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: advances during BCG shortage. World J Urol. 2022;40(5):1111-24.

- Balar AV, Kamat AM, Kulkarni GS, Uchio EM, Boormans JL, Roumiguié M, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for the treatment of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer unresponsive to BCG (KEYNOTE-057): an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):919-30.

- Liberman D, Lughezzani G, Sun M, Alasker A, Thuret R, Abdollah F, et al. Perioperative mortality is significantly greater in septuagenarian and octogenarian patients treated with radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Urology. 2011;77(3):660-6.

- Kang Z, Min X, Weinreb J, Li Q, Feng Z, Wang L. Abbreviated Biparametric Versus Standard Multiparametric MRI for Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(2):357-65.

- Lemiński A, Kaczmarek K, Gołąb A, Kotfis K, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Słojewski M. Increased One-Year Mortality Among Elderly Patients After Radical Cystectomy for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Retrospective, Observational Comparative Study. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:255-63.

- John JB, Varughese MA, Cooper N, Wong K, Hounsome L, Treece S, et al. Treatment Allocation and Survival in Patients Diagnosed with Nonmetastatic Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: An Analysis of a National Patient Cohort in England. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7(2):359-65.

Read the Abstract