G eoffrey Hinton is one of the “godfathers” of artificial intelligence, critical in the development of deep learning, backpropagation and much more. In 2024 he was awarded the Nobel prize in physics in recognition of his immense contributions to the field of computer science. Not bad for someone who started his career with the aim

A High School Student Explains How Educators Can Adapt to AI – The Markup

Hello readers,

While we’ve often used Q&As to highlight smart, innovative, or interesting takes on something, we have yet to run commentary on The Markup. But a recent piece by Bay Area high school student and journalist William Liang, published at our new home, CalMatters, has us rethinking this policy.

In his piece below, William lays bare the stark reality of how artificial intelligence has changed secondary schooling in the cradle of America’s tech sector. In short, virtually all students seem to be using AI to help do their homework, and there’s virtually no reliable way for teachers to detect when this happens.

William then offers a smart approach to fixing the problem, with both practical ideas for making sure students are learning and an inspiring vision for what school should be about now that AI is forcing a reset.

Going forward, we plan to experiment more with running commentary here at The Markup when it’s on topics we think you’ll really care about and when it strikes us as particularly illuminating.

I’ll let Wiliam take it from here.

Thanks for helping us try something new,

Ryan Tate

Editor

The Markup/CalMatters

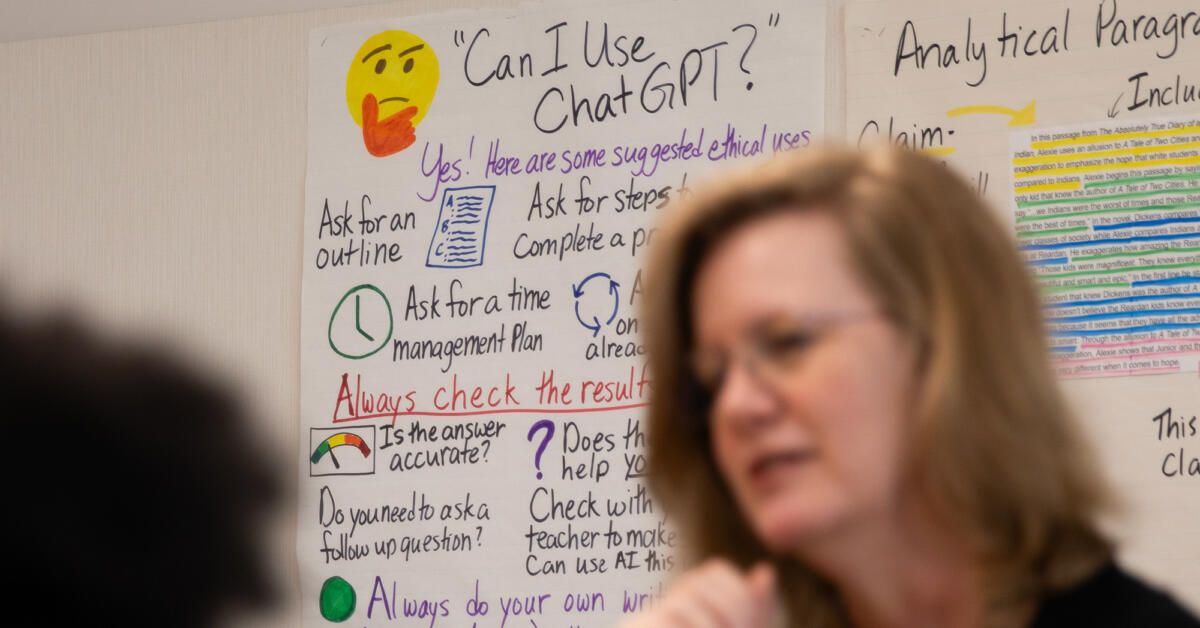

The education sector has sleepwalked into a quagmire. While many California high schools and colleges maintain academic integrity policies expecting students to submit original work, a troubling reality has emerged: Generative AI has fundamentally compromised the traditional take-home essay and other forms of homework that measure student thinking.

A striking gulf exists between how teachers, professors and administrators think students use generative AI in written work and how we actually use it. As a student, the assumption I’ve encountered from authority figures is that if an essay is written with the help of ChatGPT, there will be some sort of evidence — a distinctive “voice,” limited complexity or susceptibility to detection software.

This is a dangerous fallacy.

AI detection companies like Turnitin, GPTZero and others have capitalized on this misconception, claiming they could identify AI-generated content with accuracy levels as high as 98%. But these glossy statistics rest on the naive assumption that students submit raw, unmodified ChatGPT responses.

It’s very easy for students to use AI to do the lion’s share of the thinking while still submitting work that looks like our own.

A 2023 University of Maryland study revealed these detectors perform only slightly better than random guessing. I surveyed students at high schools across the Bay Area and found that the vast majority consistently use AI on writing tasks, regardless of detection measures. Not a single student reported submitting unaltered AI text. Meanwhile, almost all of my teachers told me they regularly overturn or disregard the AI checker’s conclusions.

The reality is sobering: It’s very easy for students to use AI to do the lion’s share of the thinking while still submitting work that looks like our own. We can manually edit AI responses to be more “bursty,” employ one of the myriad programs that “humanize” text or blend AI-generated ideas with our own prose.

The problem isn’t technological — even perfect detection software couldn’t prevent intellectual plagiarism when students can harvest ideas from AI and put them in their own words. Ultimately, the problem is behavioral.

When cheating is easy and the consequences are remote, people cheat. Noor Akbari, co-founder and CEO of Rosalyn.ai, put it perfectly: “When enough players in a competitive game can cheat with a high upside and low risk, other players will feel forced to cheat as well.”

We saw this play out during COVID when online learning made cheating ridiculously easy. One study found that cheating jumped 20% during the pandemic.

The fallout is already obvious. The latest Education Recovery Scorecard shows that U.S. students remain nearly half a grade level behind in math and reading compared to pre-pandemic levels. And while California scored much better than the national average, that’s because we were already so far behind in 2019.

Sure, AI could theoretically help learning — brainstorming ideas, assisting with editing, helping students learning English with sentence structure. But come on. Most students use it because thinking is hard and AI practically makes it unnecessary.

We now find ourselves in an absurd middle ground where academic policy in response to generative AI ignores human nature. Thankfully, many teachers are adapting. But we must face an uncomfortable truth that nearly every form of unsupervised assessment can now be compromised by AI. The only reliable solution is to fundamentally rethink our approach to student evaluation.

There’s three specific changes schools and universities could implement.

First, shift major writing assessments to supervised environments. Whether it’s a timed in-class essay, proctored computer labs or oral defense exercises where students must explain their reasoning, we need approaches that verify if students can produce and defend original thinking.

Second, we should integrate oral components into major exams. Students have to be able to explain and defend their written work through one-on-one discussions with teachers. That could help reveal gaps in understanding if they’ve outsourced their thinking.

Third, educational institutions must shift emphasis from policing AI use to explicitly teaching the cognitive processes AI can’t replace: critical thinking, creative problem-solving and effective communication. These skills are best developed through iterative practice with immediate feedback, not through homework completed in isolation.

This isn’t about resisting technological progress. It’s about ensuring educational institutions fulfill their core mission: teaching students how to think independently and communicate effectively. By acknowledging that traditional assignments no longer reliably serve this purpose, we can begin adapting our educational approaches to maintain academic integrity and prepare students for a world where human judgment remains irreplaceable.

CalMatters editors confirmed that AI was not used to help write this guest commentary. “Every word of this piece is mine,” Liang told us. Given the subject, we had to ask.