Review Shengming Zhang 1 , MSc, BSc ; Chaohai Zhang 1 , BSc ; Jiaxin Zhang 1, 2 , PhD 1School of Automation and Intelligent Manufacturing, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China 2Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Fully Actuated System Control Theory and Technology, School of Automation and Intelligent Manufacturing, Southern University of Science

AI in Education Is an Unknown, Humans Are Not

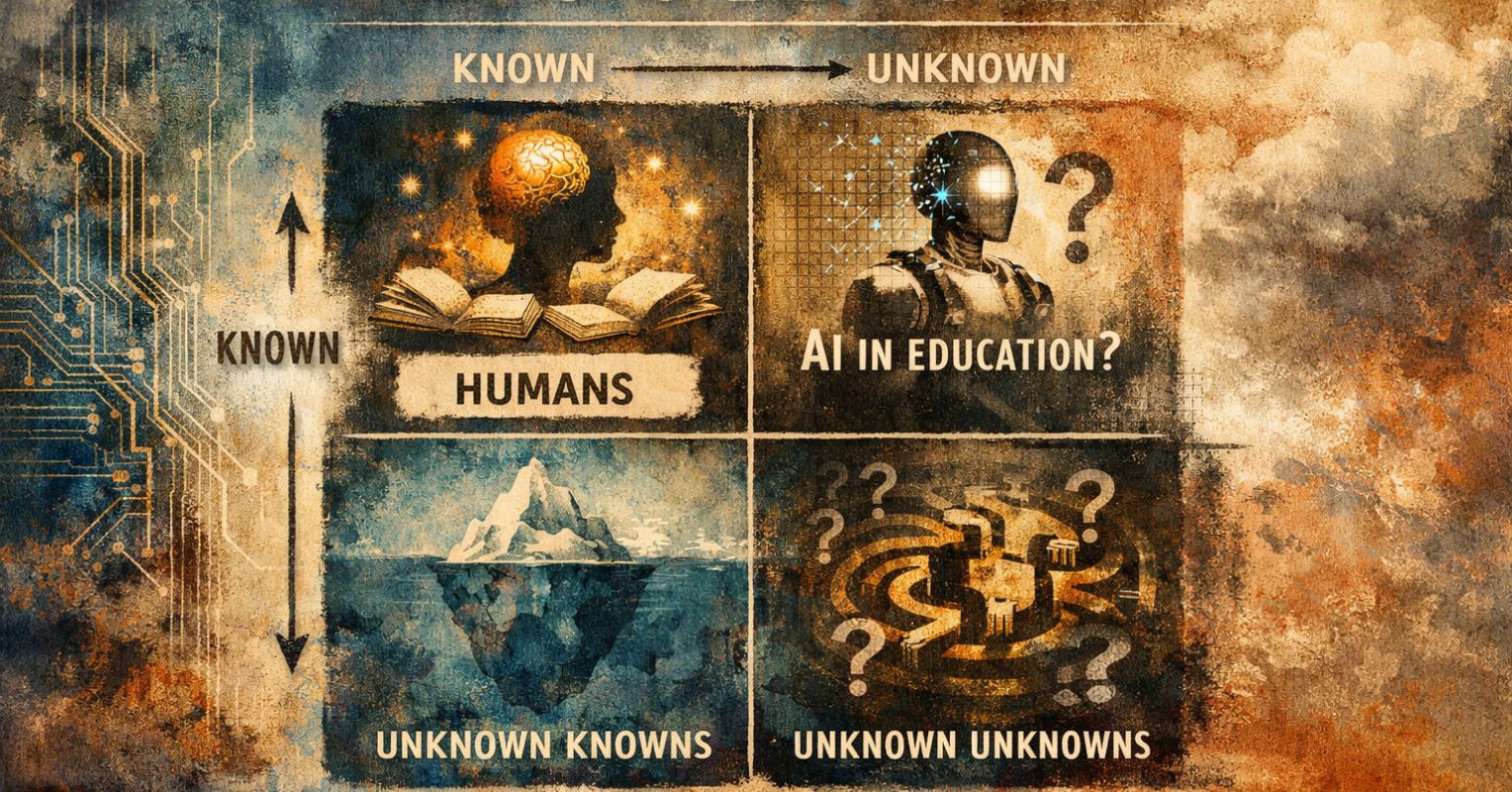

When I read Hollis Robbins’ sharp essay this week, “The Rumsfeld Matrix,” applying Donald Rumsfeld’s famous taxonomy of knowns and unknowns to the crisis in higher education, it caught my attention. Her argument: Universities are over-invested in the “known-knowns” quadrant, spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year transferring settled knowledge into students’ heads, while neglecting the quadrants where knowledge actually gets produced. With AI now capable of delivering known-known content cheaply, the case for restructuring is urgent.

It is a genuinely useful framework that expands on her proposals that I have been reading about for some time. My own views on neuroscience and the cognitive architecture of meaning-making, and Robbins’ structural lens maps onto that work in ways I find productive. She is asking where institutions should invest. I keep asking what human minds do that machines cannot. The two questions need each other.

The assumption driving AI restructuring

Robbins writes that universities “must decide which parts of known-known transfer need classroom time and which parts can be handled by cheaper, more flexible LLM systems.” The framing treats AI-delivered instruction as a settled alternative whose effectiveness is established enough to anchor a resource reallocation strategy. That assumption is everywhere right now: in policy documents, in board presentations, in the pitches that edtech companies make to provosts. Robbins herself has published a detailed technical roadmap for delivering California State University’s general education requirements through an AI-driven microservices architecture, complete with competency rubrics and automated assessment pipelines. AI works for learning. The meta-analyses say so.

A recent unpublished study calls this assumption into question.

What a comprehensive re-analysis found

František Bartoš, Oliwia Bujak, Patrícia Martinková, and Eric-Jan Wagenmakers have just released a preprint that does something no one has done before: a comprehensive re-analysis of nearly the entire published evidence base on AI and learning. They gathered 1,840 effect size estimates from 67 meta-analyses and ran them through the most sophisticated publication bias correction methods available. Bartoš developed those methods. Wagenmakers is one of the most influential methodologists in the behavioral sciences. They built the tools that the field should have been using all along.

What they found just changed that conversation.

The published meta-analyses report a median effect of 0.67, which in the social sciences counts as a substantial positive finding. That is the number driving restructuring decisions across higher education. But the published record is missing its failures. Negative results were published at roughly one-fifth the rate of positive results. When Bartoš and colleagues corrected for this bias, the effect dropped to about one-third of what had been reported. And even that diminished estimate might be zero.

But the shrunken average is not even the real problem. The chaos underneath it is. The variation between studies is so extreme that the literature cannot predict what direction a future study’s result will go. The prediction interval stretches from AI substantially hurting learning to AI substantially helping it. The evidence cannot tell us which. The literature is not “mixed.” It is incoherent.

The authors tested every plausible way to reduce that chaos: outcome type, educational field, educational level, the role of the AI system. Nothing worked. No subgroup showed consistent benefits. And there was no meaningful difference between studies published before and after January 2023. The ChatGPT-era research is just as compromised as everything that came before it.

I have seen this pattern before. The bilingual advantage debate, which I have spent years working in, has a structurally similar problem: different researchers measuring different things under the same label, publication bias inflating positive findings, and meta-analyses aggregating apples and oranges into a single impressive number. The nudging literature went through it, too. Bartoš and Wagenmakers published a devastating correction to the nudging meta-analysis in PNAS in 2022, and the evidence essentially vanished. The AI-and-learning literature is getting the same treatment now.

What we actually know works in learning

So here is the problem for this version of Robbins’s matrix. If AI-delivered instruction were a known-known, the strategic case for reallocating resources away from human instruction would be strong. But Bartoš and colleagues have shown that AI’s effects on learning do not belong in the known-known quadrant at all. They are a known-unknown at best.

Meanwhile, what does sit firmly in that quadrant?

Humans.

Human cognition is the known-known. Human meaning-making. The capacity of one mind to engage another in the friction-laden, unpredictable, embodied process through which understanding actually forms. Thousands of years of evidence that the messiness of human instruction, the tangents, the misunderstandings, the moments where a teacher reads confusion on a student’s face and changes course, is the mechanism through which deep learning occurs. It looks like inefficiency. It is actually the point.

The irony is sharp enough to cut. The sector is being told to reorganize around the one element whose effects it cannot verify, while devaluing the one element whose effects are the most thoroughly established in the history of education.

Why human teaching matters

Robbins wants to move students into the quadrants where they surface buried knowledge, conduct active research, and encounter anomalies that generate new questions. All of these require a mind that can translate between incompatible systems of meaning, detect that something does not fit, and hold contradictions without resolving them prematurely. These capacities are built through engagement with other minds. They are built through the known-known quadrant, through the human-mediated version of it specifically.

AI can deliver content. Everyone knows that. Whether content delivery, stripped of human friction, produces the cognitive conditions necessary for everything else the university is supposed to do is a completely different matter. As Bartoš and colleagues conclude: “Broad claims of generalized learning gains resulting from AI/LLMs appear premature; the current evidence is insufficient to support robust policy or practice recommendations.”

The Rumsfeld Matrix is the right framework. It just needs to be applied to AI itself. When you do that, the picture becomes much more muddled. AI in education is the unknown. Humans are the known-known. A university that forgets which is which is gambling with its future.

References

Hollis Robbins, “The Rumsfeld Matrix,” Anecdotal Value (Substack), February 2026.

Hollis Robbins, “How to Deliver CSU’s Gen Ed with AI,” Anecdotal Value (Substack), July 2025.

Bartoš, F., Bujak, O. Z., Martinková, P., & Wagenmakers, E. (2026, January 28). Effect of Artificial Intelligence on Learning: A Meta-Meta-Analysis. Retrieved from osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/h529e_v1