Using detailed surveys and machine learning computation, new research co-authored at UC Berkeley’s Center for Effective Global Action finds that eradicating extreme poverty would be surprisingly affordable. By Edward Lempinen New research co-authored at UC Berkeley's Center for Effective Global Action finds that, for a surprisingly modest investment, extreme poverty could be eradicated globally by

Donald MacKenzie · AI’s Scale

Hyperion is the name that Meta has chosen for a huge AI data centre it is building in Louisiana. In July, a striking image circulated on social media of Hyperion’s footprint superimposed on an aerial view of Manhattan. It covered a huge expanse of the island, from the East River to the Hudson, from Soho to the uptown edge of Central Park. I assumed that the image had been made by someone with misgivings about the sheer scale of the thing, but it turned out to have been posted to Threads by Mark Zuckerberg himself. He was proud of it.

The imperative to increase scale is deeply embedded in the culture of AI. This is partly because of the way the field developed. For decades, the neural networks that are the basis of much AI today – including large language models of the kind that underpin ChatGPT – were considered less promising than ‘symbolic AI’ systems which apply rules, roughly akin to those of symbolic logic, to systemic bodies of knowledge, often knowledge elicited from human experts. The proponents of neural networks took a different path. They believed that the loose similarity of those networks to the brain’s interconnected neurons and their capacity to learn from examples (rather than simply to apply pre-formulated rules) made them potentially superior as a route to artificial intelligence. Many of their colleagues thought they were wrong, especially Marvin Minsky, MIT’s leading AI expert. There was also the fact that early neural networks tended not to work as well as more mainstream machine-learning techniques.

‘Other methods … worked a little bit better,’ Geoffrey Hinton, a leading proponent of neural networks, told Wired magazine in 2019. ‘We thought it was … because we didn’t have quite the right algorithms.’ But as things turned out, ‘it was mainly a question of scale’: early neural networks just weren’t big enough. Hinton’s former PhD student Ilya Sutskever, a co-founder of OpenAI (the start-up that developed ChatGPT), agrees. ‘For the longest time’, he said in 2020, people thought neural networks ‘can’t do anything, but then you give them lots of compute’ – the capacity to perform very large numbers of computations – ‘and suddenly they start to do things.’

Building bigger neural networks wasn’t easy. They learn by making predictions, or guesses. What is the next word in this sentence? Is this image a cat? They then automatically adjust their parameters according to what the word actually turns out to be or whether a human being agrees that the image is indeed a cat. That process of learning requires vast quantities of data – very large bodies of digitally available text, lots of images labelled by human beings etc – and huge amounts of ‘compute’. Even as late as the early 2000s, AI faced limitations in these respects. A crucial aspect of the necessary computation is the multiplication of large matrices (arrays of numbers). If you do the component operations in those multiplications one after another, even on a fast conventional computer system, it’s going to take a long time, perhaps too long to train a big neural network successfully.

By about 2010, though, very big data sets were starting to become available. Particularly crucial was ImageNet, a giant digital assemblage of millions of pictures, each labelled by a human being. It was set up by the Stanford University computer scientist Fei-Fei Li and her colleagues, who recruited 49,000 people via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, which enables the hiring of large numbers of online gig workers. Also around 2010, specialists in neural networks began to realise that they could do lots of matrix multiplications fast on graphics chips originally developed for video games, especially by Nvidia.

In 2012, those two developments came together in what can now be seen as the single most important moment in the launching of AI on its trajectory of ever increasing scale. Sutskever, Alex Krizhevsky (another of Hinton’s students) and Hinton himself entered their neural network system, AlexNet, into the annual ImageNet Challenge competition for automated image-recognition systems. Running on just two Nvidia graphics chips in Krizhevsky’s bedroom, AlexNet won hands down: its error rate was 30 per cent lower than the best of its more conventional rivals.

The lesson was quickly learned: if you give neural networks ‘lots of compute’ by using graphics chips, then ‘suddenly they start to do things.’ For a couple of years after 2012, the number of graphics chips that a typical research project used was still modest: no more than eight. But as the interest in neural networks shifted from academia to tech companies, and from research to the development of AI models designed for practical use, scale began to grow exponentially. Jaime Sevilla and Edu Roldán of the research institute Epoch AI calculate that since the early 2010s, the amount of computation used to train state-of-the-art models has been increasing by between four and five times annually. Fourfold annual growth implies sixteen-fold over two years, 64-fold over three years and so on. That, in essence, is how you get from Krizhevsky’s bedroom to Manhattan-scale data centres.

Nowhere is the imperative of ever increasing scale pursued more dedicatedly than at OpenAI, set up in 2015 by a group including Sutskever, Elon Musk and Sam Altman. ‘When we started,’ Altman has said, ‘the core beliefs were that deep learning [neural networks with lots of ‘layers’] works and it gets better with scale.’ There was a ‘like, religious level of belief … that that wasn’t going to stop’. The series of increasingly big language models developed by OpenAI gave its researchers data that they were able to use to check that the firm’s ‘like, religious’ belief was empirically justified. Writing in January 2020, they outlined evidence that the accuracy of the models’ predictions got better as their scale increased: ‘Language modelling performance improves smoothly as we increase the model size [the number of parameters], dataset size and amount of compute used for training … We observe no signs of deviation from [these] trends at large values of compute, data or model size.’

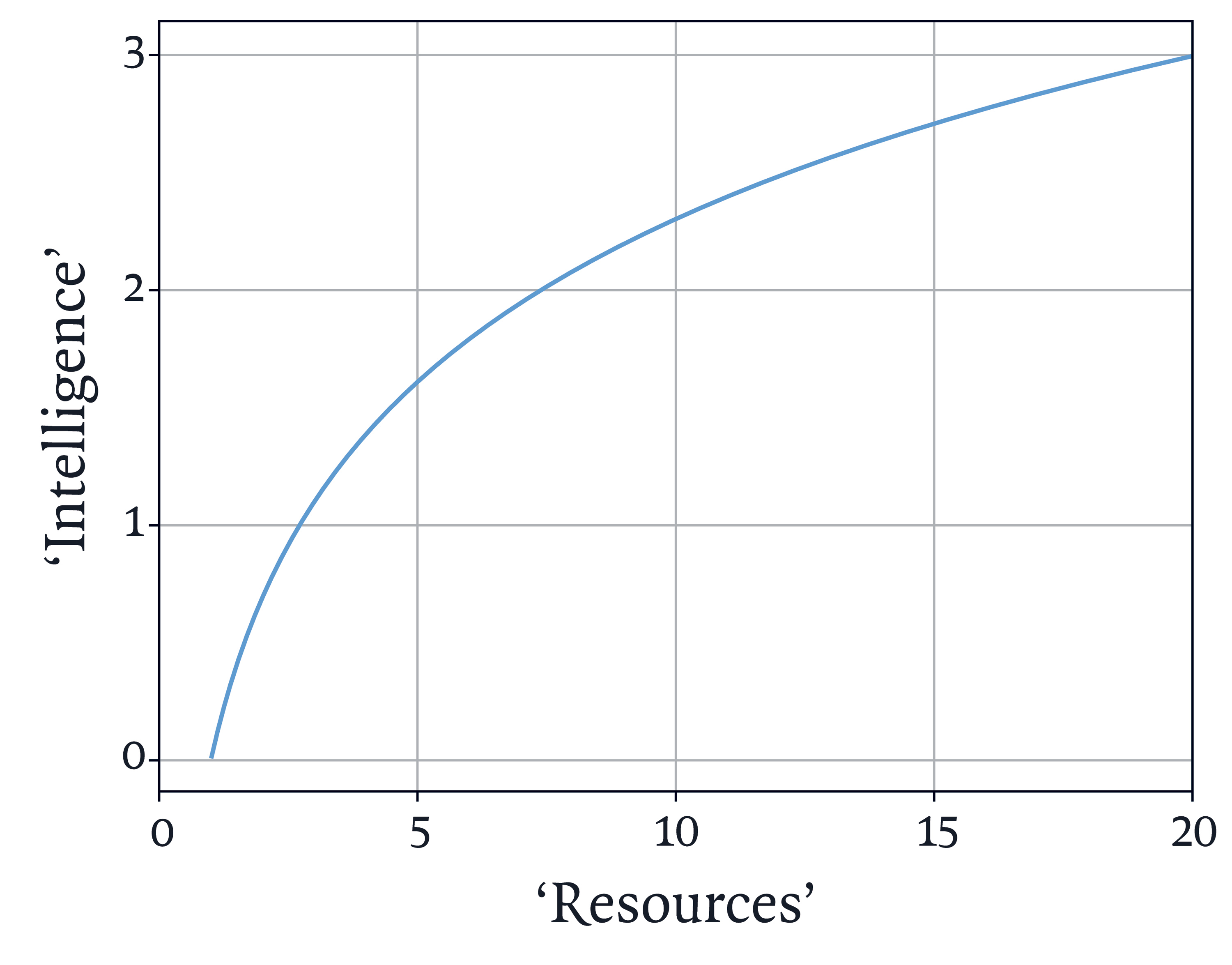

OpenAI’s faith in ‘scaling laws’ of this general kind remains strong. As Altman put it in a blog post in February last year, ‘the intelligence of an AI model roughly equals the log of the resources used to train and run it … It appears that you can spend arbitrary amounts of money and get continuous and predictable gains; the scaling laws that predict this are accurate over many orders of magnitude.’ The ‘laws’ may of course break down – they are empirical generalisations, not laws of physics – but they are worth taking seriously because ‘arbitrary amounts of money’ are indeed being shelled out on the infrastructure of AI. In August, researchers for Morgan Stanley estimated that $2.9 trillion will be spent globally on data centres between 2025 and 2028, while Citigroup has estimated total AI investment globally of $7.8 trillion between 2025 and 2030. (For comparison, the US defence budget is currently around $1 trillion per year.)

One little word, though, in Altman’s blog post should give us pause: ‘log’. A logarithmic function, at least of the kind that is relevant here, is characterised by diminishing returns (see the graph). The more resources you put in, the better the results, but the rate of improvement steadily diminishes. One reason to keep going regardless may well be the widespread sense that AI is a ‘winner takes all’ business, and so having the best models (by even a small margin) will bring disproportionate rewards, perhaps even de facto monopoly. Another motivation seems to be the hope that small improvements in performance will suddenly give rise to a dramatic qualitative change: the emergence of ‘artificial general intelligence’ or maybe even ‘superintelligence’.

However, in Sutskever’s view the availability of human-created data on which to train AI systems is already a big constraint. ‘Compute is growing,’ he says. ‘The data is not growing, because we have but one internet … data is the fossil fuel of AI. It was like created somehow, and now we use it, and we’ve achieved peak data, and there’ll be no more.’ It’s not a nuanced claim, but the specialists I have spoken to don’t dismiss it out of hand. It’s true, one of them told me, that soon ‘we’ll be data constrained,’ but he also raised the prospect that AI systems may themselves be able to create reliable new data to replenish humanity’s over-exploited reservoirs: ‘What we don’t know is, do we cross the threshold where AI produces novel training data effectively? … If we get to that threshold, then we are going to have superintelligence. We’re very close. I don’t think people understand how close we are, I don’t think anyone wants to think about it.’

Another researcher I have spoken to, Lonneke van der Plas, who is a specialist in natural language processing, implicitly warns of the risk of training AI models on computer-generated data. Among the languages on which she works is Maltese, which has only around half a million native speakers. Much digitally available Maltese, she tells me, is low-quality machine translation. In consequence, she says, if you go all out for scale in developing a model of Maltese ‘you get a much worse system than if you carefully select the data’ and exclude the reams of poor-quality text.

AI’s scale doesn’t matter just to specialists. The rest of us are being taken on a ride along the logarithmic curve too. The graphics chips and data centres on which ‘arbitrary amounts’ are being spent require huge quantities of electricity to power them. Some of this is coming from renewable sources, but much of it involves burning natural gas or sometimes even coal. Just one of the many new gas-fired power plants that are being constructed in the US to meet the growing demands of data centres is on the site of an old coal-fired power station near Homer City, Pennsylvania. When it is up and running it will generate 4.4 gigawatts, just a little more than the peak winter electricity demand for the whole of Scotland.

The International Energy Agency reckons that if the current global expansion of data centres continues, the CO2 emissions for which they are responsible, currently around 200 million tonnes per year, will be about 60 per cent higher by 2030. In a rational world, new AI data centres would be built only where ample renewable electricity is available to power them. But in a reckless race along the diminishing-returns curve, whatever fuel is immediately available will tend to get used. In the US, that still mostly means natural gas; in China, it’s coal. Investors, many of whom are uneasy about the trillions of dollars being spent on AI infrastructure, oscillate between the fear of missing out on continuing gains on AI stocks and the fear that AI is a bubble. No one can say with certainty if, or when, the bubble will burst. If it does, it will be a financial market trauma, but from the viewpoint of the planet it might be better sooner rather than later.