Author: Scott Rouse, Features Writer Top 5 Over 20 years ago, I sat in a lecture hall while a professor talked excitedly about artificial neural networks (ANNs) and their potential to transform computing as we knew it. If we think of a neuron as a basic processing unit, then creating an artificial network of

Multimodal AI-powered Nanosensor Platforms for Non-invasive Breathomic | NSA

Introduction: Towards AI-Powered Nanosensors for Breathomics Diagnostics

The rising medical needs of the exponentially growing global population are overwhelming current diagnostic and healthcare facilities. It raises demand for innovations at all three crucial stages of disease management, including advanced preventive strategies, point-of-care diagnosis, and personalised and precision medicine.1–4 Emerging diseases, diseases of critical concern, epidemics, and pandemics (such as cancer, monkeypox, coronavirus disease, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental health issues) have further raised the standard of innovation due to their respective significant challenges.5–9 To tackle these health conditions, screening, diagnosis, and prognosis are important steps that can be enhanced to achieve better patient outcomes in terms of associated morbidity and mortality. Consequently, the global health landscape is witnessing a paradigm shift toward point-of-care, personalised, and non-invasive diagnostic technologies.3,10–12

Conventional diagnostics, including blood tests and biopsies, have been the essential pillars of medical diagnosis, but their inherent bottlenecks are becoming evident.10–12 These procedures are often invasive, require sophisticated handling by trained manpower, and are centralised, resulting in prolonged turnaround times and high costs. This creates a significant gap in global efficacy to conduct large-scale population screening or frequent monitoring, particularly for diseases that necessitate early-stage detection, especially for cancer, respiratory diseases and infectious outbreaks.10,11

It has created a pressing requirement for innovative and affordable diagnostic tools, a trend reflected in the global market. For instance, the global breath biopsy testing market, a key sector of this new diagnostic panorama, was valued at around $1.42 billion in 2025 and is anticipated to reach $2.39 billion by 2034, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.97%.13 This growth rate is a clear indicator of the increasing need for affordable, innovative, and non-invasive solutions, as a substantial percentage of healthcare professionals now support these technologies, overcoming medical hesitancy to replace conventional diagnostics.14

Such increasing demand has led to the emergence of breathomics, a field that encompasses the comprehensive examination of biomarkers, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs), in exhaled breath.15–18 The human exhaled breath is a dynamic and complex biomarker mixture containing thousands of gases/VOCs. Majorly, VOCs are gaseous byproducts of metabolic activity, arising from endogenous pathways, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and microbial metabolism, as well as exogenous exposures, such as pollutants and dietary intake.15–18 These breath biomarkers provide a real-time “breathprint” of an individual’s health. For instance, an elevated acetone level in exhaled breath (between 0.9–1.8 ppm) is associated with diabetes, and certain alkanes and aldehydes are linked to lung cancer, while altered hydrogen levels indicate irritable bowel syndrome.19–21

However, the transformation of breathomics from laboratory to clinical application has been generally obstructed by three key challenges.14,22 First includes the detection of extremely low, parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) concentrations of disease-specific breath biomarkers, which is beyond the limit of conventional tools. Second is specificity towards particular biomarkers due to their diversified spectrum in exhaled breath (more than 3000). Finally, there is the complex, heterogeneous, and high-dimensional nature of the data they produce, due to the impact of diet, lifestyle, environment, and comorbidities.23 This combination of chemical complexity and data heterogeneity underscores the need for both advanced materials and intelligent analytical frameworks.

These challenges are being addressed by integrating modern technologies, primarily data science, artificial intelligence, and nanotechnology.17,24–27 A powerful synergy between these rapidly growing technological fields has given rise to AI-powered nanoscale diagnostic (AND) platforms based on nanosensors. Metal oxide semiconductors, graphene, carbon nanotubes, MXenes, borophene, and hybrid nanocomposites based nanosensors exhibit exceptional sensitivity and selectivity, which are required to detect trace VOCs with high accuracy.19–21,28–36 This is due to their exceptional physicochemical properties, including high surface-to-volume ratios, tunable electronic/optical band gaps, and catalytic activity, which make them distinctly suitable for detecting weak metabolic signals.32–40 Furthermore, sensor miniaturisation due to the inclusion of nanotechnology further allows the development of portable, wearable, field-deployable and point-of-care (POC) devices, providing access to diagnostics outside centralised facilities.3,12 For instance, multi-sensor nanomaterial-based arrays have successfully screened for lung cancer in different controlled studies and field trials,25,37 demonstrating their practical viability.

However, the raw data from nanosensor arrays are usually complex, multidimensional, and noisy, consisting not only of biological signals but also of environmental variabilities and inherent sensor drift.2,38 This is where AI and data science emerge as crucial tools to address the third challenge. Advanced machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms can filter noise, correct drift, and extract subtle and nonlinear patterns hidden within sensor data.18,39–44 Additionally, integration of innovative techniques such as network analysis and time series analysis can help in finding the intrinsic correlations amongst the different variables within the sensor data set.45,46 A remarkable example is the “Breath AI” platform developed at City University of Hong Kong, which combines high-resolution mass spectrometry with neural network algorithms, at an estimated cost of only $10–15 per test.47

However, despite this synergy, a substantial research gap remains. There is a need for larger, standardized, and clinically validated datasets to train robust and generalizable AI models from AND platforms.14,22 Numerous existing studies rely on trivial and heterogeneous cohorts, which limit the algorithm’s efficacy in being reliably implemented across diverse patient populations and environmental settings. Furthermore, standardised protocols for human breath collection, storage, and analysis are still deficient, leading to difficult cross-study assessments.14,22 Clinicians require explainable AI (XAI) and advanced models, integrated with network analysis, to understand the diagnostic rationale from AND platforms, which is critical for building reliability and ensuring regulatory approval.48 Difficulties with data privacy, regulatory approval, and the scalable manufacturing of AND platforms remain to be fully addressed. Besides, the “black-box” nature of many ML models presents a substantial challenge to their real-time applications and clinical acceptance.15,16,49,50

This review intends to offer a comprehensive and exhaustive examination of these AND Platforms for screening/diagnosing various diseases/disorders. It will first outline the principles and topical developments in nanoscale sensors personalised for VOC recognition. Next, it will detail the data science and AI approaches that highlight robust pattern recognition and predictive analytics. It will highlight the diversified applications of AND platforms across key disease domains, including respiratory, metabolic, oncological, and neurological conditions. More importantly, it will critically assess the challenges related to their clinical translation, including the need for robust standardisation, regulatory approval, and scalability, and provide a prescriptive, forward-looking solutions, with a focus on XAI, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), and advanced network theory. Overall, this review aims to provide a cohesive roadmap for advancing AND technologies from experimental innovation to reliable clinical tools.

Fundamental Overview of AI-Powered Nanosensor Diagnostic Platforms with Breathomics Applications

The real-time clinical translation of breathomics depends on the development of highly sensitive and reliable sensing AND platforms. This section highlights the fundamental hardware of the AND platforms for breathomics, examining the biological origin of breath biomarkers and the innovative nanotechnology engineering for their detection with advanced applications.

Principles of AND Breathomics Platforms

Fundamentally, breathomics is based on the examination of VOCs in exhaled breath to find an individual’s physiological state.51–53 The foundational principles of breathomics include metabolic origin, disease-specific signatures, non-invasiveness, and temporal and spatial resolution.54 The human body is a complex biochemical system, and its numerous metabolic activities yield a huge array of compounds/VOCs. Volatile byproducts of these activities are transported through the bloodstream to the lungs, where they are ejected with each exhalation.24,55–57 The profile of these VOCs/compounds helps as a “breathprint” that reflects the body’s current state. Variations in metabolic pathways due to a disease can result in changes in the concentration, ratio, or even the presence of specific VOCs.55,57–60 The variation in concentration of disease-specific VOCs is used to distinguish the healthy and affected individuals. For instance, cancer cells have altered metabolic requirements (known as the Warburg effect), which can result in the production of specific VOCs, such as toluene and isoprene, while acetone is linked to diabetes.19,21,50,61–66 The challenge is that these variations are frequently indirect and comprise a collective response of several VOCs rather than a single compound. Besides, the spatial and temporal analysis of breath biomarkers helps in understanding the prognosis of diseases, which is helpful in designing personalised and precise healthcare through AND platforms.

A complete AI-powered nanosensor AND platform is a multi-layered system that decodes these breathomics principles into a functional diagnostic device. It comprises three interconnected layers, including the sensing layer, the data acquisition and processing layer, and the AI-driven analytics layer (Figure 1). The sensing layer is the physical interface where the exhaled breath sample is collected and converted into a measurable electrical signal (the hardware). The centre of this layer is a nanosensor or an array of highly sensitive nanosensors, each with a slightly different response profile.65–70 This is the layer where nanotechnological engineering comes into play and plays a crucial role in VOC detection. A spectrum of nanomaterials, broadly classified as metal-based, ceramics-based, polymer-based, biomaterials-based, carbon-based, and their hybrids with different morphologies of nanostructures, have been tested for AND platforms enabled breathmoic detection of various diseases.19,21,34,35,67–76 Majorly, semiconducting metal oxides, such as those of tin, zinc, titanium, tungsten, and silver, as well as ternary oxides, have been popular for designing AND platforms due to their tunable band gaps and high ambient stability.29,67,77–81 However, requirements of high temperature operation have limited their commercial viability in terms of complicated design, increased cost and energy requirements.82,83 It has shifted the paradigm towards carbon-based nanostructures such as carbon nanotubes and graphene due to their high conductivity. However, their functionalization and processing are tedious, and they exhibit lower ambient stability.84–86 On the other hand, organic and biomaterials are less stable in ambient conditions, affecting the lifetime and repeatability of designed AND platforms.87–90 This has led to the exploration of novel nanomaterials and their architectures, including metal-organic frameworks, MXenes, borophene, black phosphorus, and green nanomaterials.23,91–96 However, their exploration is in its infancy and requires support from further experimental and clinical validation. Besides, advanced nanocomposites, hybrids, and heterostructures of multiple nanomaterials are also popular due to the synergy between the merits of their precursors for breathomic AND platforms.19–21,69,97–99

|

Figure 1 Three layers of AND platforms with “the hardware layer”: sensing material, substrate and electrodes, where material engineering plays a vital role, “the linking layer”: Data acquisition and processing to convert physical signals to digital signals, and “the software layer”: data science and AI-driven analytic layer, which functions as brain of AND platforms based on pretrained algorithms with the help of AI, ML and other data modelling tools. |

Since the target of these sensors is exhaled breath, which consists of more than 3000 breath biomarkers, using a single AND platform is insufficient to manage and decode all the signals.99–105 Consequently, rather than relying on a single AND chip, these platforms use an array of semi-selective nanosensors. Each nanosensor interacts differently with a given mixture of VOCs present in exhaled breath, creating a unique “fingerprint” or signature for the targeted disease. For instance, lung cancer is associated with specific sets of biomarkers, including benzene derivatives, aldehydes, ketones, aromatic hydrocarbons, and nitrogen-containing compounds, which are linked to various metabolic changes in the body due to lung cancer.65,106–108 It necessitates the use of a sensor array rather than a single sensor to detect such a diverse set of breath biomarkers for screening lung cancer. These sensor arrays use diversity over specificity, mimicking the human olfactory system to generate complex signal fingerprints, essential for targeted disease detection.63,68,100,101

The data acquisition and processing layer is the critical link between the physical world and the digital one. The raw sensing signals from the nanosensors are frequently noisy, subject to baseline drift, and can be manipulated by environmental factors such as humidity and temperature.14,22 This layer is accountable for data cleaning and normalization to avoid noise in sensing signals and target the main dataset. They are like data preprocessors that consist of noise reduction algorithms to filter out electrical noise and other artefacts, baseline correction to address sensor drift, and normalisation to arrange data for robust downstream analysis.108–112

Data science and AI-driven analytic layer (the software) is the brain of the AND platforms, where trained AI algorithms convert the preprocessed sensor data into actionable clinical insights.102,103 This layer enables the AND platform to not only identify the presence of VOCs but also to decipher their complex patterns in the context of targeted diseases. It utilises various ML, DL and complex sciences techniques (such as network analysis) to decode the sensing data into actionable outcomes. For instance, ML techniques such as random forest recognise diagnostic patterns across breath profiles, whereas network analysis aids in revealing the information layer by layer, addressing the problem of the black box nature of conventional ML techniques.27,43,45,104 Besides, RL and DL handle complex temporal and high-dimensional data and capture the complex dynamics in VOC fluctuations.27,105 Together, these three layers work concurrently when an AND platform is subjected to human breath, enabling the distinction between healthy and affected individuals in an affordable, accessible, and adaptable manner.

Applications of AND Platforms for the Breathmoic Detection of a Wide Spectrum of Diseases

The synergy of nanosensors and AI has pushed breathomics from a research interest into a powerful diagnostic tool with a broad range of clinical applications. This synergy of results in modern-age AND platforms such as electronic nose (E-Nose), which has been utilised for various disease detection such as respiratory diseases, cancer, infectious diseases, metabolic and neurological disorders, and cardiovascular diseases.65,106–112

Respiratory diseases are a common target for breath-based AND-device enabled diagnostics, as the disease conditions directly affect the composition of exhaled breath.113–117 AND platforms can detect small variations in volatile breath biomarkers that indicate inflammation, infection, or physical/operational damage to the lungs. For instance, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are characterised by airway inflammation and obstruction.118,119 The exhaled breath of patients with these diseases comprises raised levels of specific VOCs, including nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide and a distinctive profile of short-chain hydrocarbons.120–122

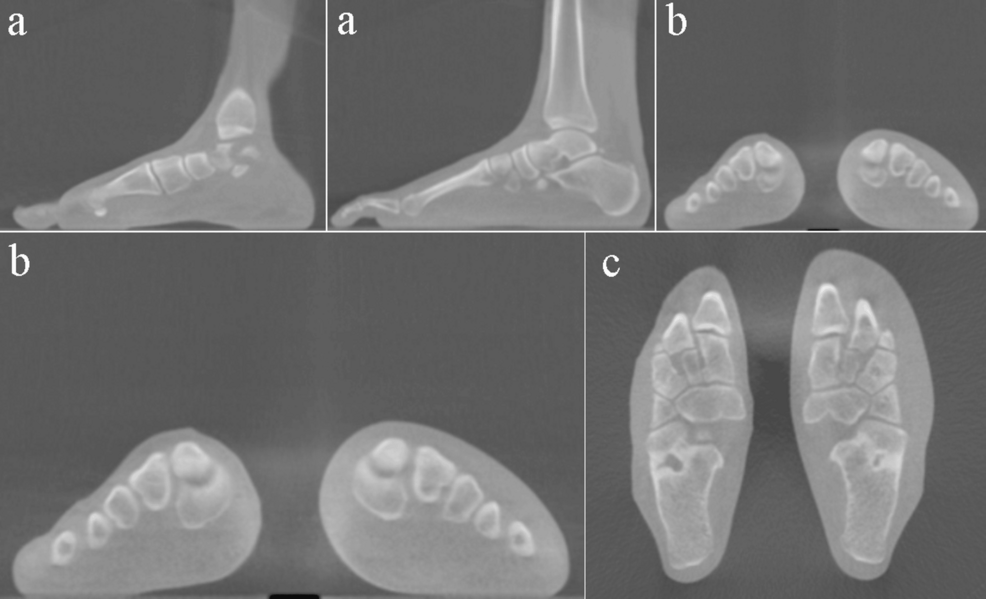

For instance, Drera et al33 reported an AND platform (E-nose) consisting of a sensing array comprised of eight nanosensors made up of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) in association with a combination of principal component analysis (PCA), support vector machine (SVM) and linear discrimination analysis (LDA) for COPD detection (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 AND platform to detect COPD breath biomarker (ammonia) with (a) an individual sensor device, (b) a sensor array forming the AND device, (c) an individual sensor scheme readout, (d) Variation in resistance with respect to time on interaction with COPD biomarker ammonia for eight different sensor array (pristine SWCNTs, UV-functionalized, functionalized with DNA oligonucleotide, α,α′-dihexylquaterthiophene, perylene-3,4,9,10-tetracarboxylic-dianhydride, polyaniline, tris(4-carbazoyl-9-ylphenyl)amine and 4,4′-cyclohexylidenebis [N,N bis(4-methylphenyl) benzene-amine] for two different ammonia concentrations: 15.9 ppm and 8.1 ppm, respectively, with exposure for 180s, (e) breath sampling setup showing change in resistance with time recorded by the eight sensors array for 180 s exposure to an exhaled breath sample from a healthy individual, and (f) Identification ratio represented by dotted line and accuracy index denoted by solid line for PCA-SVM in black color and LDA in red color, estimated for diverse datasets. Reproduced with permission from33 Copyright 2021 RSC. |

The AND platform was exposed to well-known breath biomarkers of COPD, including ammonia (NH3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), as well as two cross-signal-generating gases: hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and benzene (C6H6). The selectivity of the AND platform and its efficacy in distinguishing between four biomarkers were established using PCA analysis. The device was also tested in clinical scenarios by exposing it to exhaled breath samples from COPD patients and healthy control volunteers. A combined technique of PCA, SVM, and LDA approaches demonstrated that the fabricated AND platform can be trained to distinguish healthy subjects from COPD subjects with considerable accuracy, despite the comparatively limited dataset. It exhibited an accuracy index of 0.97 and 0.90 for LDA and PCA, respectively. The strength of this method suggests its prospective applications in harsh environments where control over strict sample collection procedures is not possible.

The utilisation of AND platforms is not limited to controlled settings but extended to clinical diagnosis of respiratory diseases.54,57,123 Recently, Yin et al123 reported an ultrasensitive chemiresistive AND platform comprising a sensing layer of Ag-decorated ZnO and algorithms based on pattern recognition using the SVM technique. It was employed to detect fractional exhaled NO2 with H2S as an interfering analyte, showing detection limits of 5 ppb and 50 ppb for NO2 and H2S, respectively, which enabled differentiation of these asthma biomarkers in exhaled breath. In a clinical trial with 80 exhaled breath samples, the AND platform efficaciously differentiated 40 healthy controls from 40 asthma patients by examining a distinctive “fingerprint” of these biomarkers. An SVM algorithm used for classification exhibited a significant overall accuracy of 81%. The platform’s efficacy to detect disease severity was further confirmed by a strong correlation (r = −0.74) with the clinical standard of diurnal peak expiratory flow variation and (r = −0.98) with a commercial electrochemical NO2 sensor. They also integrated Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to reveal the fundamental mechanisms underlying the nanosensor’s ultra-sensitivity, providing a theoretical basis for the AND platform’s high performance. This study demonstrated that the use of an AND platform can efficiently translate complex breath data into a reliable diagnostic tool for clinical practice.

Yadav et al124 showed the use of an AND platform for the rapid, single-shot detection and classification of multiple respiratory viruses. They integrated a SERS sensor based on a highly sensitive silver nano-sculptured thin film with an ML algorithm. The sensor provides a powerful SERS enhancement factor of 1011, allowing the detection of viral fingerprints in clinical nasal and nasopharyngeal samples. It was designed to classify five respiratory viruses, including Influenza A, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Human Rhinoviruses, and two SARS-CoV-2 variants (Omicron and Delta). Several ML algorithms were tested for analysis and classification, with a Multilayer Perceptron model exhibiting the best performance. The AI model achieved a notable 5-fold validation accuracy of around 97.61%, with a test accuracy of around 97.47%, a sensitivity of 97%, and a specificity of 99%. The AND platform’s fast response time of just 11 minutes makes it highly appropriate for clinical implementation, demonstrating the use of the AND platform for rapid virus detection and aiding in the efficient management of respiratory infections.

Although conventional ML models have demonstrated significant efficacy in classification tasks, the complex, high-dimensional, and temporal characteristics of sensor array or network data suggest that advanced DL models may provide enhanced and detailed solutions. These models are capable of independently extracting hierarchical features from raw sensor data, frequently eliminating the necessity for manual feature engineering. A recent study presented an innovative wearable electronic skin based on the AND platform that non-invasively monitors physiological data for telemedicine.125 The AND platform’s core is an artificial epidermal device that mimics the skin’s hierarchical structure by in-situ growing Cu3(HHTP)2 particles onto a hollow spherical Ti-MXene surface. This bionic nanosensor can independently detect NO2 gas and pressure and offers acoustic signature perception and Morse code communication (Figure 3). They have employed Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to examine the complex characteristics of sensor data (Figure 3d). The response curves from a sensor array over time (during the transient phase) have been treated as a 1D “image”. A 1D-CNN employs a convolutional filter to “slide” across this time-series data, learning to recognize specific motifs and temporal patterns. It includes the rate of signal increase, the “peak” response time, or the recovery slope, which are highly indicative of certain VOCs. When utilized with an array of sensors, the resulting data can be represented by a two-dimensional matrix (Sensor ID x Time). This configuration enables a 2D convolutional neural network (2D-CNN) to effectively analyse the complex spatio-temporal features, capturing both individual sensor responses and the evolution of patterns across multiple sensors simultaneously. As a result, the AI component of the platform, an ML algorithm, enables a wearable alarm system with a mobile application terminal to accurately assess asthmatic risk factors. The system efficiently connects external NO2 exposure with abnormal breathing and activity, attaining 97.6% recognition. This study described an AND platform that integrates bionic nanomaterials and AI to enable next-generation telemedicine diagnostics.

|

Figure 3 Flexible wearable alarm system based AND platform for examining asthma: (a) Diagram of the flexible smart wearable AND platform, which comprises an ESP32 chip (1), dual-mode sensor (2), power supply (3), and supports wireless data transmission via WIFI (4); (b) Optical image illustrating the integration of a flexible dual-mode sensor into flexible printed circuits for detecting different pressure levels, (c) Real-time response of the wearable alarm system to: (i) exposure to NO2 atmosphere; (ii) normal and (iii) deep breathing; (iv) light and (v) heavy pressing; (d) Schematic diagram illustrating the basic structure of one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1-D CNNs); and (e) The confusion matrix for five patterns: S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 represent light breathing (normal), deep breathing (wheezing), light and heavy pressing (limb weakness), and NO2 atmosphere to worsen asthma situation, respectively. Reproduced with permission from,125 Copyright 2024 Springer Nature. |

A critical challenge in breathomics, particularly for wearable sensors, is long-term temporal drift, where a sensor’s baseline or sensitivity changes over time. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their more advanced variants, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks, are specifically designed to model sequential data and long-term dependencies.126–129 Additionally, an RNN can be trained to “remember” the sensor’s state from previous measurements, enabling it to model and correct for temporal drift. This model enables transition from single-snapshot diagnostics to continuous health monitoring, as it can distinguish between newly identified biomarkers of clinical significance and predictable sensor drift.

A more direct application is in modelling the complex and non-linear dynamics of gas sensing itself. For instance, Lim et al129 demonstrated the use of a sparse Recurrent Neural Network (SRNN) with a 2×4 SMO-based gas sensor array. By introducing a novel feature for the dynamics of current (ΔI), the SRNN model effectively captured the rapid and competing adsorption/desorption processes of gas molecules. This advanced model, which leverages the RNN’s ability to process temporal dependencies, successfully distinguished between intuitively indistinguishable datasets of gas species (NO2, HCHO, and a mixture) with up to 92% accuracy. This highlights the efficacy of RNNs to process complex, real-time sensor dynamics for applications in mixed gas environments, such as breath analysis.

Besides, a major bottleneck in breathmoics is the scarcity of large and labelled clinical datasets. Training complex DL models on limited data often leads to overfitting. Generative models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), are a powerful tool for data augmentation.130–132 It can be trained on a limited set of real patient breath “fingerprints” to generate new, synthetic yet realistic sensor data. This augmented dataset, which combines real and synthetic data, can then be used to train a more robust and generalizable diagnostic classifier. It addresses the issue of small sample sizes in clinical validation. This data augmentation strategy has proven highly effective in parallel diagnostic fields that face similar data scarcity. For example, a recent study on diagnosing COPD used non-invasive respiratory sounds rather than breath VOCs. The researchers employed a CycleGAN model to augment their dataset of breathing-cycle sounds, thereby enhancing data diversity.132 This data augmentation, combined with advanced deep learning models (InceptionV3), led to a remarkable 99.75% F1-score in classifying COPD. This case study presents a clear model for breathomics, suggesting that a GAN-based method can enhance small nanosensor array datasets to improve the reliability and accuracy of diagnostic models.

There is a critical need to differentiate between bacterial and viral respiratory tract infections, which has been tackled by a recent study.133 The AND platform is based on a graphene-based e-nose sensor array, which is specifically modified with metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and metal phthalocyanines to improve its efficacy to detect disease-specific VOC biomarkers from exhaled breath. The developed system showed preliminary success in differentiating between simulated bacterial and viral infections. Notably, the platform was clinically validated using 145 patient samples and achieved a high diagnostic accuracy of 83.7% in the validation group, with an Area Under the Curve of 0.87. An external clinical trial with 43 patients showed 75.7% accuracy. The AI component of the platform, a weighted fusion classification model integrating SVM, Random Forest, and Lasso regression, played a crucial role in converting the sensor’s electrical response fingerprints into a precise diagnostic outcome. This study highlights that the use of the AND platform can effectively guide appropriate treatment decisions, support precise medicine and reduce antibiotic misuse by providing a fast and accurate differential diagnosis.

The application of AND platforms has been extended to lung cancer screening and diagnosis in different modules such as acoustic, optical, electrochemical, resistive and stress sensors.26,100,134–147 For instance, Saeki et al100 recently reported an AND platform based on a nanomechanical sensor array that consists of a membrane-type surface stress sensor integrated with ML for screening lung cancer. The array consisted of 12 channels with different receptor materials, which generated 12 waveform signals from one exhaled breath sample. The perioperative variations in the expiratory waveform signals from every channel were represented by boxplots and analysed through a Mann–Whitney U examination. The trials included 57 subjects, and an ML model was developed using the RF technique and compared with the outcomes of logistic regression and SVM analyses. The optimal accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, negative predictive value, and positive predictive value were found to be 0.809, 0.807, 0.830, 0.812, and 0.806, respectively. The AND platform provides a substantial prediction efficacy for finding the presence of lung cancer in patients who have undergone lung cancer surgery. These outcomes recommended the potential of AND platforms for lung cancer screening. However, it faces challenges in the precise signalling pattern of sensor responses to lung cancer breath biomarkers from patients and its specificity towards lung cancer, which can be further addressed by an integrated examination of a fabricated AND platform, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, and proton transfer reaction-mass spectrometry.

On the other hand, Tran et al148 designed a chemiresistive AND platform with a sensing layer of hybridised porous zeolitic imidazolate (ZIF-8) comprising laser-scribed graphene and MOF inspired by human lungs (Figure 4). The platform was tested using simulated breath samples comprising four dominant VOCs, including acetone, ethanol, methanol, and formaldehyde, which are metabolomic signatures of lung cancer. The high performance of the AND platform was supported by ultra-fast response times of 2–3 seconds, a wide range of detection from 0.8 ppm to 50 ppm, and significant selectivity at room temperature. To further improve diagnostic efficacy, the platform employed a multilayer perceptron (MLP)-based ML algorithm. This AI component attained a remarkable accuracy of around 96.5% in classifying the four target biomarkers. This study’s accomplishment in addressing the challenge of correctly predicting multiple biomarkers using a single chemiresistor emphasizes its potential for personalised wearable sensors and its application in economical telehealth and POC monitoring for lung cancer screening.

|

Figure 4 Schematic illustration of the ZIF-8@LSG chemoresistor-based AND platform for VOC lung cancer biomarker detection from human breath, supported by machine learning augmentation: (a) Depicts the roadmap illustration of the ML classification from ZIF-8@LSG-based AND platform and confusion matrix graph for eight sets of lung cancer different breath biomarkers by means of: (b) MLP classifier algorithm for 0.8–10 ppm concentrations of VOC biomarkers of lung cancer, and (c) RBF classifier algorithm for 0.8–10 ppm concentrations of VOC biomarkers of lung cancer in human breath. Reproduced with permission of,148 Copyright 2024 RSC. |

Since there are many breath biomarkers associated with lung cancer, each of them represents a different metabolic process and can aid in identifying its prognosis. For instance, dyspnea and respiratory failure associated with lung cancer can be characterised by breath formaldehyde. Recently, Zhang et al149 reported a chemiresistive AND platform based on Co3O4 nuclei-encapsulated ZnO-based yolk–shell spheres integrated with a multi-layer perceptron and extreme learning machine algorithm based on deep neural network (DNN) foundations to identify formaldehyde for lung cancer screening. The physics of detection in terms of the adsorption of formaldehyde over the AND platform was explained using DFT.

These platforms have also been integrated with IoTs like smartphones to detect different biomarkers for lung cancer. For instance, Cao et al150 recently reported a fluorescence-type AND platform made of a ratiometric fluorescent probe material (Tb-UiO-67 (8:1)) integrated with a smartphone for detecting isoprene and cyclohexanone for lung cancer screening. It realised significantly low limits of detection (LODs) of 0.58 ppb and 3.95 ppb for cyclohexanone and isoprene, respectively. The platform’s efficacy in differentiating between these two breath biomarkers is based on two distinct mechanisms: fluorescence quenching by cyclohexanone due to its high electronegative nature, and a Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer mechanism. Additionally, fluorescence improvement is achieved by isoprene, primarily through absorbance-derived enhancement of both mechanisms. The study further integrated this technology into a smartphone-connected AND platform, which visually identified the biomarkers with different colour variations. The outcomes of the study also established the probe’s low cytotoxicity and good biocompatibility, which is a step towards green sensors.

The applications of AND platforms are not limited to the detection of lung cancer and extend to different types of cancer.26,43,151–159 Recently, Liu et al160 reported an AND platform based on a bioinspired biosensor array of MXene/DNA composite integrated with ML (neural network algorithm) for pilot screening of cancer patients by identifying exhaled gas samples from diverse populations. The platform was used to distinguish between breath biomarkers of stomach cancer, lung cancer, intestinal cancer, and healthy subjects, with accuracies of 86.3%, 94.1%, 89.5%, and 86.3%, respectively. On the other hand, Xie et al26 demonstrated the use of a surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)-based AND platform based on plasmonic metal-organic frameworks nanoparticle film. This platform addresses the challenge of differentiating between lung and gastric cancer using volatile biomarkers (aldehyde). The exhaled breath samples were collected from 1780 subjects, including healthy individuals and patients with lung and gastric cancer. The sensor data was analysed using an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and DL algorithm, which attained over 89% diagnostic accuracy. The ANN model’s feature extraction technique efficiently identifies small differences in VOC composition in breath samples from different subjects. This study validates effective noninvasive diagnosis of multiple cancers using AND breathomic platforms and introduces a method for investigating disease characteristics using SERS spectra of exhaled breath, addressing a significant clinical need.

Cai et al158 reported an innovative AND platform comprising a paper-based field-deployable nano-optoelectronic nose integrated with a smartphone for the detection of breath VOCs of gastric cancer. The sensor array employs nanoplasmonic materials and chemically responsive dyes to identify VOCs at parts-per-billion (ppb) levels (Figure 5). The AND platform is designed to be low-cost, with nanosensors priced at 25¢ per test and accessories at approximately $30. When combined with an AI-based pattern recognition algorithm, specifically orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis, it established a 90% accuracy in differentiating between individuals with gastric cancer and healthy controls.

|

Figure 5 (a) Diagram of the paper-based smartphone optoelectronic nose-based AND platform for cancer biomarker detection from human breath: (i) Various dyes and nanoparticles modified porous nylon filter paper for the sensing of VOC biomarkers of cancer from human exhaled breath, (ii) Colour variations in the array were observed using a smartphone, which was operational with a 3D-printed holder, mini diaphragm pump, and Schlenk flask, and (iii) The OPLS-DA algorithm was employed to generate an RGB variance diagram differentiating gastric cancer patients from healthy subjects. (b) Monitoring of exhaled breath in healthy subjects and gastric cancer patients: (i) (1) Conventional GC-MS spectra of exhaled breath from healthy individual and gastric cancer patients: (2) 25 VOCs biomarkers were observed in breath of gastric cancer patients including butanal, isoprene, pentanoic acid, phenol, hexanoic acid, 2-methyl-, benzaldehyde, dodecanal, 1-hexanol, phenyl ester, 2-ethyl-, acetic acid, 1-pentanone, hexane, nonanal, decane, benzoic acid, levomenthol, decanal, propanal, nonadecanol, 7-hexadecenal, octadecane, tetradecane, 2-pentanol, heptadecane, cedrane and acetone, (ii) Example of sensor array colour variations after exposure to exhaled breath of (1) a healthy individual and (2) a gastric cancer patient, (iii) Breath fingerprint patterns attained from the sensing response of the AND array to exhaled breath of (1) healthy individual and (2) gastric cancer patients, and (iv) (1) OPLS-DA graph of the sensitivity to 40 healthy subjects and 40 gastric cancer patients; (2) The ROC graphs shaped employing the OPLS-DA algorithm. Reproduced with permission from,158 Copyright 2023 Elsevier. (License Number: 6095860765733). |

Conversely, Sharifi et al161 developed an innovative AND platform, in the form of a portable and paper-based E-nose, capable of rapid and on-site detection of gastric cancer malignancy through the analysis of VOCs from tissue samples. The platform employs eight types of fluorescent metallic nanoclusters immobilised on a paper substrate as sensing elements. It showed distinct fluorescence changes when exposed to VOCs from both cancerous and noncancerous tissues of 22 subjects. By applying chemometric techniques like PCA and partial least squares discriminant analysis, the platform achieved a 95% accuracy rate in differentiating between fresh cancerous and normal tissue samples. This optical e-nose enables fast intraoperative diagnosis in healthcare settings, providing results within under four hours, which aligns with the typical anesthesia recovery period.

Recently, Luo et al156 extended this concept for the detection of oral cancer using an SERS-based nanosensor based on Ag nanowires, which is enabled by a plasmonic covalent organic framework film integrated with DL analysis using the Light Gradient Boosting (LGB) algorithm. This design enhances SERS signals and improves biomarker adsorption for both gaseous and liquid analytes, such as methyl mercaptan (a breath biomarker) and uric acid (a Saliva biomarker), without requiring pretreatment. Using a deep learning LGB algorithm on combined SERS spectra from breath and saliva, the platform attains 98% accuracy in screening oral cancer. Concurrently, a recent study reported a highly versatile AND platform for the non-invasive diagnosis of multiple cancers, using a novel mimetic biosensor array (MBA).18 The AND platform’s core is an array of biosensors fabricated using a self-assembly technique of peptides and MXene, which exhibited a considerably enhanced sensing response up to 150% greater than pristine MXene. The MBA was integrated into a real-time testing platform and, with the aid of ML algorithms, effectively distinguished and identified 15 different odour molecules across five chemical classes. More notably, the platform was clinically validated by analysing breath samples from volunteers in four groups, including healthy individuals and patients with lung cancer, upper digestive tract cancer, and lower digestive tract cancer. The ML-driven analysis achieved exceptional diagnostic accuracies of 100%, 94.1%, 90%, and 95.2% for each group, respectively.

The application of the AND diagnostic platforms has also been used to address the challenges related to diabetes diagnosis and monitoring.19,21,98,162–167 For instance, Ansari et al105 presented a novel AND platform for the non-invasive diagnosis of diabetes by detecting breath acetone, a key biomarker correlated with blood glucose levels. The platform’s core is an α-Fe2O3-multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) nanocomposite sensor, which was specifically developed to operate effectively even in the high humidity of human breath. The optimized sensor demonstrated a strong response of 5.15 to 10 ppm of acetone at 200 °C, along with excellent selectivity and fast response times. To enhance the platform’s reliability, a deep learning algorithm was employed to analyze breath samples from 50 volunteers, accounting for various factors influencing acetone levels. This AI-driven analysis yielded a diagnostic accuracy of nearly 85% with a low error margin of ±15%. The device, powered by a rechargeable battery, proves to be a suitable candidate for continuous, non-invasive blood glucose sensing, demonstrating how an AND platform can effectively translate chemical sensor data into a reliable diagnostic tool for managing metabolic disorders.

On the other hand, another study presented a highly selective AND platform for diabetes monitoring based on a low-cost and flexible sensor made from MoS2 on Ti-MXene, integrated with AI.168 The platform is a novel integration of the piezotronic effect, where applied external strain enhances sensor response and uses it as a sensing signal for excellent acetone detection at room temperature. Importantly, the AI component, using PCA and binary logistic regression, allowed the selective detection of acetone from eight other common breath VOCs. A recent study reported a novel AND platform for the multi-stage screening and staging of obesity-induced Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, addressing the challenge of requiring stage-specific biomarkers.169 This AND platform integrated SERS using composite silver nanowires with highly optimised and interpretable ML models (Figure 6). They acquired 72,600 Raman fingerprint signals from the plasma of 242 participants, including healthy controls, glucose-intolerant individuals, obese individuals, and diabetic patients. The ML component, uses a Quadratic Support Vector Machine (SVMs) and achieved an optimal multi-stage classification accuracy of 94.5%, effectively discriminating all four progression stages. The study used SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to interpret the ML model’s decisions, identifying the Raman shifts related to stage-specific biochemical changes and providing information about disease progression.

|

Figure 6 Roadmap summary of the SERS-AI-enabled AND platform for multi-stage screening and staging of obesity-related type-2 Diabetes Mellitus: (a) Plasma samples from healthy individuals and those with three type-2 Diabetes Mellitus states (obese, glucose-intolerant, diabetic) were examined by SERS technique integrated with ML, (b) Training, validation, and interpretation steps including Quadratic SVM, improved via 10-fold CV, attains the best performance, verified on a distinct set, and deduced using shapley additive explainers together with 17 additional classifiers and DL models for comprehensive comparison. Reproduced with permission from,169 Copyright 2025 Elsevier, (License number: 6095870143095). |

Breath ammonia serves as a critical biomarker for individuals with various chronic conditions, including chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, hepatic encephalopathy and urea cycle disorders.69,111,170–173 A dedicated study describes an AND platform developed to address issues related to humidity and breathing motion in breath ammonia sensing.172 This multimodal AND system integrates three distinct sensors, including an ammonia sensor based on a thermally cleaved conjugated polymer, a humidity sensor using reduced graphene oxide, and a breath dynamics sensor based on a 3D folded strain-responsive mesostructure. This configuration enables the platform to continuously detect the diagnostic ranges of ammonia under humid breath conditions for more than three weeks. The AI-powered component of the system, a K-means clustering algorithm, decodes the multimodal signals from these sensors to constantly distinguish between the breath of healthy individuals and those with elevated ammonia concentrations. The on-body testing further confirms the AND platform’s operational ease and practicality, highlighting its significant potential for non-invasive and continuous tracing of ammonia biomarkers for various chronic illnesses.

Similarly, Volatile amines detected in exhaled breath serve as diagnostic biomarkers for renal and hepatic disorders. Gaur et al174 presented a highly advanced AND platform for the non-invasive diagnosis of kidney and liver diseases, using the analysis of volatile amines in breath. The AND platform’s core is a chemiresistor array based on a tungsten diselenide/MWCNT nanocomposite, which exhibited high selectivity and sensitivity. This platform operates at room temperature and attains ultra-low theoretical LODs, including 387 ppt for triethylamine and 157 ppb for methylamine. The platform’s efficacy to discriminate among a mixture of volatile amines and other breath VOCs is its most significant feature. An integrated ML algorithm was employed to analyze the sensor array’s data, attaining a high accuracy of around 94% in discriminating between various volatile amines and their mixtures.

With technological advancements, these AND platforms have been fabricated using biogenic routes and integrated into smart masks for efficient, real-time, and on-site disease detection.73,175–178 A recent study reported a novel AND platform in the form of a paper-based, biodegradable e-nose integrated directly into a face mask.179 They developed a design that addresses the issue of high humidity in breath analysis by using a hydrophobic polymer coating, helping the sensors remain unaffected by moisture (Figure 7).

|

Figure 7 (a) Monitoring outcomes of AND platforms to varying humidity levels, including 0%, 70%, and 95% RH, and to a mixture of humidity and isopropyl alcohol, showing the AND platforms’ robustness to varying humidity, (b) Schematic illustration of variation of sensitivity with the polarity of breath VOCs, demonstrating that higher polarity outcomes in a shallow response, (c) Working principle of the AND device based on the adsorption of VOC biomarkers resulting in the swelling of the polymer layer, which rises junction resistance, (d) Diagrammatic illustration, (e) Photograph of a smart face mask incorporated with AND platform for real-time breath analysis, (f) Normal and deep breathing patterns observed through the AND platform-integrated face mask, validating rapid response and recovery with change in breathing response on: (g) alcohol consumption and (h) smoking, (i) Biodegradable nature of the AND platform-integrated face mask in the time span of 280 days exhibiting its green characteristics. Reproduced with permission from,179 Copyright 2025, Wiley. |

The AND platform enables real-time breath monitoring for a range of applications, including a representative use case for Tuberculosis detection. A pre-trained DL model achieved 89% accuracy in diagnosing Tuberculosis and tracking patient recovery. In addition to diagnostic applications, the platform uses a fully biodegradable, paper-based sensor that breaks down in soil within months. The research shows that an AND platform can integrate environmentally friendly components with AI technology to deliver a non-invasive and sustainable option for personalized healthcare and disease detection.

On the other hand, Wang et al180 introduced a novel AND platform to provide a non-invasive and wearable solution for individuals suffering from hoarseness and aphonia. The platform is a humidity-sensing respiratory microphone which uses gold nanoparticle-based humidity sensors integrated into a standard face mask (Figure 8). This system uses nanoparticle-polymer interfaces to turn slight changes in breath humidity into accurate electrical sensing signals. This platform uses a CNN to decode respiratory patterns into clear speech. It attained a high speech recognition accuracy of 85.61%, effectively translating breath patterns into verbal communication without requiring vocal cord activities. By integrating advanced nanosensors with DL, this AND platform introduces a contactless and non-invasive approach in assistive speech technology for voice rehabilitation and human-machine interaction.

|

Figure 8 Demonstration of a convolutional neural network-enabled breath language recognition for diagnosing modality: (a) Convolutional neural network modules employed for respiratory language schemes, (b) Schematic of the data processing method, (c) Best accuracy graphs of training in black dots and validation data in green dots, (d) Confusion matrix from data of five volunteers attaining accuracy of around 85.61%, (e) AND platform identifies the exhaled breath signal only during the speaking motion by the volunteer. Reproduced with permission from,180 Copyright 2025, Wiley. |

Moreover, AND platforms have been reported with advanced and innovative applications, which are giving them new dimensions to support society. Recently, Xiang et al181 presented a highly innovative AND platform that overcomes the major limitations of conventional E-noses to allow portable and wearable applications. The AND platform is based on a single-sensor, multifunctional E-nose system that integrates a micro-electromechanical system (MEMS) gas sensor with a flexible printed circuit board. The primary sensing material, comprising ZnO-ZnSnO3 raspberry-like microspheres, showed improved gas selectivity by employing a dual-temperature modulation strategy. Notably, the AI module uses the MiniRocket algorithm for gas classification, enabling efficient feature extraction and streamlined processing that are well-suited for real-time operation on embedded devices. The wearable AND platform accurately classified and predicted levels for eight breath VOCs and introduced a silent communication feature that converts breathing rates into Morse code, advancing human-machine interaction. By integrating advanced sensor materials with efficient AI, this work established a robust technological framework that combines portable gas detection with silent communication (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Comprehensive Summary of Studies Performed to Develop Innovative AND Nanosensors and Their Applications in Monitoring Diverse Health Conditions |

Alternatively, these AND platforms integrate wearable devices for real-time data collection, nanosensors to improve accuracy and sensitivity, and ML to quickly and precisely analyse large-scale health data. This integrated approach can translate “big health data” into proactive health management strategies, moving from diagnosis to analysis to prevention.183 By integrating wearable nanosensors with smart algorithms, the AND platform provides personalised, comprehensive healthcare aimed at addressing growing health issues and economic challenges associated with an ageing population.183 These prospects have introduced a new paradigm of AND platforms for digital-age applications, featuring advanced features that cater to conventional diagnostics and techniques.

Key Challenges to Clinical Adoption and Commercialisation

Although AND platforms hold great promise for precision medicine, telemedicine and next-generation personalized diagnostics, they possess major challenges of clinical adoption and commercialisation.175,182,184–186 Effectively addressing these challenges is critical to advancing future research and development initiatives. The key challenges include analytical and clinical validation, sensor specificity and selectivity, data quality and standardisation, regulatory hurdles and clinical acceptance, and cost and scalability.

A primary challenge associated with AND platforms is the absence of standardised protocols for sample collection, storage, and analysis.176–178 Disparities in breathing patterns, sample humidity, and the presence of environmental contaminants can influence sensor signals, which may result in variations in measurement outcomes.76,187 This makes it challenging to associate findings across different studies and institutions. Besides, the absence of large-scale and multicenter clinical trials limits regulatory approval and clinical trust.76,188,189 Although nanosensors are sensitive, they may not always have the specificity required to identify individual biomarkers among the numerous VOCs present in breath. Cross-sensitivity to various VOCs or environmental factors may cause false positives or errors in diagnosis.76,176,178 While AI can reduce some noise, sensor selectivity remains a primary challenge.177,178

The success of AI models is mainly dependent on the quality and quantity of training data. Most studies use comparatively small datasets, which limits the models’ generalizability.176–178 Developing AI models that are robust and generalizable for use across diverse patient populations is challenging.177,178 Diagnostic platforms must obtain regulatory approval from organisations like the Food and Drug Administration before they are widely used. The “black-box” nature of many AI/DL models makes this difficult, as clinicians and regulators require an understanding of the diagnostic reasoning.49 Without XAI, it is challenging for doctors to trust a diagnosis, and regulatory bodies may be uncertain to approve AND platforms whose decision-making processes are opaque.48,49 Moreover, while some AND platforms are cost-effective, the research and development related to these advanced nanomaterials and AI models is expensive. Making these technologies accessible for large-scale population screening, particularly in settings with limited resources, remains a concern.76,176–178

A further significant challenge is the disparity often observed between AI model predictions and gold-standard laboratory validation.23,190 Although a model may achieve high classification accuracy on a separate test set, this does not replace thorough validation using established analytical techniques, such as Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS). This gap is further broadened by discrepancies between in-vitro sensor testing (like using gas cylinders) and complex in-vivo clinical breath samples, which are complicated by humidity, temperature, and a matrix of thousands of confounding VOCs. This “bench-to-bedside” gap means that models often fail to generalise from a controlled lab environment to a chaotic clinical one, hindering real-world adoption.23,190

Besides, a significant source of “false” information stems from a lack of control over confounding factors during setup and sampling.23,190 Sensor array data can be disrupted by many factors unrelated to the target disease. Environmental exogenous VOCs, including pollution, cleaning agents, and perfumes, may add considerable noise.23,190 Furthermore, endogenous (but non-pathological) factors heavily influence the breath profile. A patient’s recent diet (such as the intake of garlic or coffee), smoking status, alcohol consumption, and current medications can generate VOCs that may interfere with or resemble disease biomarkers. The sampling procedure can potentially introduce challenges, including contamination from the sampling bag or tube, or improper collection techniques (such as capturing mouth air instead of alveolar air), may compromise the clinical value of the data. If confounders are not rigorously standardized, the platform may generate inaccurate fingerprints, which can result in incorrect AI predictions.23,190

Bridging the Gap: Future Solutions and Prospects

These challenges, although significant, can be addressed through dedicated interdisciplinary efforts and innovative solutions based on digital-age technologies.191–197 The formation of an international consortium dedicated to developing uniform protocols for the collection and processing of breath samples is a crucial preliminary measure. This will allow the formation of large, high-quality, and publicly accessible databases of breathomics data. Such an accessible repository would be important for training and validating more robust AI models and advancing current models. Future research should emphasise the development of highly selective nanosensor materials using advanced engineering techniques, such as surface engineering, hetero-atom engineering, hybrid engineering, defect engineering, and band-gap engineering.191–197 It includes designing hybrid nanomaterials and incorporating biomimetic elements, such as peptide- or DNA-modified sensors, to increase binding specificity to target breath VOCs.198–201 The integration of multisensory arrays, such as optical, electrochemical, and chemoresistive sensors, can also provide a more comprehensive data “fingerprint”. To address the “black box” problem, the future of AND platforms will depend on the integration of advanced data modelling, which includes XAI, network theory, and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs).

From Black Box to Explainable AI (XAI)

Explainable AI (XAI) is a crucial tool for examining the black box nature and inferring a model’s output. It is essential to shift the focus from merely listing approaches to examining their specific and practical applications within the sensor-array context. For example, while simple approaches like feature permutation can rank sensor significance, they fail to find the complex inter-sensor relationships or the direction of a sensor’s contribution. This raises the need for more advanced data-modelling approaches.48,202–205 Local-agnostic approaches, such as LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), can estimate a complex model’s decision for a single prediction.45,202,206–209 However, the most robust global approaches, such as SHAP are more powerful, which attribute a precise “contribution” or “importance” value to each feature (sensor) for every given prediction, based on game theory.204,205,210 The identification of sensor features which contributed most to a diagnosis using SHAP provides a valuable layer of interpretability and builds clinical trust.204,205,210 It allows researchers to quantitatively distinguish which sensor and, by extension, which specific nanomaterial’s chemical interaction contributed most significantly to a classification (like “lung cancer patient” vs “healthy”). It can be presented as a “force plot” for an individual patient or a summary plot displaying the most predictive sensors across the array.

Furthermore, if XAI reveals which sensors are steadily responsible for the maximum predictive efficacy, the insight can guide the in-silico design of smaller, cost-effective, and dedicated next-generation sensor arrays.204,205,210 On the other hand, if a sensor shows high importance along with high variability, XAI can flag it for additional examination into its chemical stability and drift characteristics. Peng et al211 adopted an integrated approach that utilises a dual-encoder network and pyramid pooling, incorporating SHAP-derived feature importance, to enhance the predictive efficacy of lung health diagnosis using exhaled gas. In 5-fold cross-validation, the developed model attained an accuracy of around 96.40%, which was efficient in distinguishing the effects of smoking and COPD amongst various individuals.

Network Theory for Sensor Array Optimization

Sensor arrays and networks are inherently dynamic, complex and high-dimensional systems.38,212–214 Examining them with conventional statistics, which treat each sensor’s time series as independent, overlooks a significant amount of information. It can be addressed by modelling the sensor array as a dynamic complex system or network graph.45,206,207,215–218 In this context, each sensor in the array is represented as a “node,” and the “edge” weights between nodes can represent the signal interrelationship amongst them. This relationship can be defined in numerous ways, including a simple Pearson correlation, a more complex time-lagged mutual information score, or covariance. The resulting weighted adjacency matrix, Aij, represents a unique “fingerprint” or topological signature for a specific disease state or an individual’s baseline breath profile. This network-based paradigm offers novel solutions to persistent hardware and analytical challenges, including diagnosing sensor drift, identifying redundancy, and performing dynamic transient analysis.

Beyond interpreting a model’s “black box,” network theory provides a powerful tool for understanding the hardware itself.45 Rather than abstractly representing the array, a concrete multiplex network framework can be used. In this methodology, PCA is first employed to reduce data dimensionality. This data is then used to construct multiplex networks where each layer is a correlation-based planar maximally filtered graph (PMFG) corresponding to a distinct gas. This approach enables the analysis of the network’s topological characteristics with time. For instance, Bhadola et al45 found that clustering coefficients exhibited consistent local connectivity for ethanol and ethylene (stabilising near 0.71) but a decreasing activity from 0.70 to 0.56 for acetone, revealing gas-specific signatures. Importantly, this approach can diagnose sensor drift and sensitivity (Figure 9). The highest path length was examined during the initial phase, with a common decrease over time, demonstrating a decrease in sensor sensitivity.45

|

Figure 9 Weighted adjacency matrices for each layer of the multiplex network observed at various time points. Reproduced with permission from,45 Copyright 2025, IEEE. |

Additionally, this network analysis can identify relationships between sensors. The analysis of multidegrees across different gases discloses both unique and mutual connectivity patterns.45 For instance, a high multidegree (such as 001110) may exhibit simultaneous unique features in sensor responses for ammonia, acetaldehyde, and acetone, while other patterns (such as between ethylene and ammonia) show strong similarities.45 This methodology, by examining developing topological properties, offers a robust tool for diagnosing sensor drift and identifying shared/unique sensor interactions, making it a versatile tool for multivariate sensor data analysis.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

A promising tool for improving robustness in breathomic models is the use of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs).219–225 Conventional AI models are purely data-driven, which can result in overfitting and physically unlikely predictions, particularly with the inadequate, high-noise, and high-dimensional datasets typically found in clinical studies.225–228 PINNs integrate known physical laws directly into the model, usually by transforming the loss function as: LTotal = LData + λLPhysics. The LData term is a standard data-mismatch term (such as mean squared error), while the LPhysics term is a “physics residual”.229–233 This residual is expressed from the governing partial differential equations or ordinary differential equations that describe the system. There are numerous governing laws, but specifically for breathomics, they include Fick’s laws of diffusion for mass transport, the Langmuir-Hinshelwood model for sensor kinetics (like analyte-sensor surface binding), equations for heat transfer for thermodynamics and Navier-Stokes equations for modelling the flow of the breath sample within the device chamber.224,232,233 This approach utilises physics as a regulator, allowing the model to learn from sparse, “small data” by leveraging the “big data” of established physical chemistry. It provides models that are not only accurate but also more robust, generalizable, and less prone to unphysical predictions (such as predicting a negative concentration or a response time faster than diffusion limits).229–233

Beyond this, if given a sparse, noisy sensor response (the data), the PINN-based model could be trained to solve for an unknown parameter in the governing differential equation, such as the specific binding affinity of a new biomarker by finding the Langmuir constant.229–233 It also enables the sensor to estimate physical parameters, not just output a classification. While computationally more expensive to train, PINNs represent a path toward models that are constrained by the real world, providing more reliable outputs, particularly when extrapolating to new patient populations or unseen environmental conditions.229–233 For instance, Wang et al234 reported a vertical graphene nanosheet-based ammonia sensor with a detection limit of 36 ppb at room temperature, which is superior to that of typical flexible sensors (50–500 ppb) at room temperature. To address the issue of the inherently slow response of the carbon-based conventional sensors, a PINN was developed by embedding Langmuir adsorption–desorption kinetics into the model architecture. The PINN decreased the sensor’s response time by approximately 50% while maintaining 96% prediction accuracy towards 1 ppm NH3 concentration. This integration of vertical graphene nanosheets, ppb-level sensitivity, and PINN modelling highlights how PINNs can bridge experimental sensing and predictive modelling, enabling real-time, wearable NH3 monitoring for breath analysis.

Future Outlook

The real potential of AND platforms is not just in diagnosis but also in continuous health monitoring and precision medicine.4,175,184,186 Future wearable devices could provide real-time alerts for chronic conditions, enabling proactive health management and informed prognosis for timely interventions.191–193 The integration of these platforms with telemedicine and remote patient monitoring systems will be key to creating a truly personalised healthcare and accessible, affordable, and acceptable ecosystem.184,185,188

Furthermore, the incorporation of wearable, continuous-monitoring AND platforms may facilitate the development of a digital twin that accurately reflects a patient’s real-time metabolic state.235–238 This approach could facilitate a transition from reactive diagnosis to predictive and personalised health management, enabling the detection of deviations from a designated healthy baseline before the appearance of symptoms appear.

To achieve this goal, several computational challenges must be addressed. Deploying advanced AI models on low-power edge devices is necessary to support data privacy and enable immediate feedback.239,240 Addressing these challenges will require innovative approaches such as neuromorphic computing chips that mimic the brain’s efficiency, advanced model quantization techniques to reduce the size of DL networks, and federated learning strategies that enable collaborative model training without transferring sensitive health data from users’ devices.241,242 In the long term, these platforms may be integrated into comprehensive “closed-loop” therapeutic systems.243–245 A detected biomarker signature may initiate an automated therapeutic response, such as sending a signal to an insulin pump, adjusting the dosage of an inhaled corticosteroid, or providing a personalized lifestyle recommendation through a smartphone application, thereby transitioning from diagnostics to automated theranostics.

Besides, integrating breathomics data with other health metrics from wearable devices like heart rate, blood oxygen levels, and physical activity can provide a more holistic and accurate analysis of a patient’s health.184,188 It is anticipated that platforms will integrate these diverse data streams to improve diagnostic accuracy and deliver a more comprehensive assessment of patients’ overall health. Although there are ongoing challenges, the integration of nanoscience and AI has the potential to impact diagnostics. Addressing standardisation, data quality, and clinical validation will be crucial steps in advancing AND platforms from research settings to clinical practice, with potential implications for precision, accessibility, and personalisation in healthcare (Figure 10).

|

Figure 10 Challenges, alternative solutions and prospects associated with next-generation AND platforms for breathomic diagnosis of critical diseases and infections, along with advanced human-machine interactions. |

Conclusion

In conclusion, the convergence of nanosensors, data science, and AI has led to a transformative paradigm of AI-powered nanosensors for breathomics diagnostics platforms. These platforms offer a non-invasive, cost-effective alternative to conventional diagnostics, utilising the analysis of volatile organic compounds to provide real-time health insights. By addressing the core challenges in standardisation, data quality, and clinical validation, these platforms are poised to revolutionise personalised medicine, moving from the laboratory into wearable devices for proactive disease monitoring and management.

The field has already shown significant promise, with platforms achieving high diagnostic accuracy for conditions such as lung cancer, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, renal disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases, and reaching sub-ppb detection limits for key biomarkers. The continued integration of robust nanomaterials, the advanced AI modelling strategies outlined here, and large-scale clinical validation will be the key drivers in creating a new healthcare ecosystem defined by precision, accessibility, and personalization.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge their institute for constant support. This research project has been supported by Mahidol University (Fundamental Fund: fiscal year 2025 by National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF)).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts attached to this work.

References

1. Kim J, Campbell AS, de Ávila BE-F, Wang J. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(4):389–406. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0045-y

2. Lipsitz LA. Understanding health care as a complex system. JAMA. 2012;308(3):243. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.7551

3. Liu W, Yue F, Lee LP. Integrated point-of-care molecular diagnostic devices for infectious diseases. Acc Chem Res. 2021;54(22):4107–4119. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00385

4. Mani S, Lalani SR, Pammi M. Genomics and multiomics in the age of precision medicine. Pediatr Res. 2025;97(4):1399–1410. doi:10.1038/s41390-025-04021-0

5. Kwong GA, Ghosh S, Gamboa L, Patriotis C, Srivastava S, Bhatia SN. Synthetic biomarkers: a twenty-first century path to early cancer detection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(10):655–668. doi:10.1038/s41568-021-00389-3

6. Lum FM, Torres-Ruesta A, Tay MZ, et al. Monkeypox: disease epidemiology, host immunity and clinical interventions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(10):597–613. doi:10.1038/s41577-022-00775-4

7. Huang H, Fan C, Li M, et al. COVID-19: a call for physical scientists and engineers. ACS Nano. 2020;14(4):3747–3754. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c02618

8. Ruiz-Pacheco J, Castillo-Díaz L, Arreola-Torres R, Fonseca-Coronado S, Gómez-Navarro B. Diabetes mellitus: lessons from COVID-19 for monkeypox infection. Prim Care Diabetes. 2023;17(2):113–118. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2023.01.008

9. Gautam A, Chaudhary V. Theranostic Applications of Nanotechnology in Neurological Disorders. Springer Nature Singapore; 2023; doi:10.1007/978-981-99-9510-3

10. Reddy N, Kattimani V, Swetha G, Meiyazhagan G. Diagnostic techniques: clinical infectious diseases. In: Evolving Landscape of Molecular Diagnostics. Elsevier; 2024:201–225. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-99316-6.00002-0

11. Markandan K, Tiong YW, Sankaran R, et al. Emergence of infectious diseases and role of advanced nanomaterials in point-of-care diagnostics: a review. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2022:1–89. doi:10.1080/02648725.2022.2127070

12. Ongaro AE, Ndlovu Z, Sollier E, et al. Engineering a sustainable future for point-of-care diagnostics and single-use microfluidic devices. Lab Chip. 2022;22(17):3122–3137. doi:10.1039/D2LC00380E

13. Global growth insights. Breath biopsy testing market size, share, growth, and industry analysis, by types (VOC analyzers, breath biopsy kits, breath sampler, others), by applications (hospitals, clinics, diagnostics laboratories, others), and regional insights and forecast to 2034.

14. Talreja RK, Sable H, Chaudhary V, et al. Review—challenges in lab-to-clinic translation of 5 th /6 th generation intelligent nanomaterial-enabled biosensors. ECS Sensors Plus. 2024;3(4):041602. doi:10.1149/2754-2726/ad9f7e

15. Ates HC, Dincer C. Wearable breath analysis. Nat Rev Bioengineer. 2023;1(2):80–82. doi:10.1038/s44222-022-00011-7

16. Vasilescu A, Hrinczenko B, Swain GM, Peteu SF. Exhaled breath biomarker sensing. Biosens Bioelectron. 2021;182:113193. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2021.113193

17. Sharma A, Kumar R, Varadwaj P. Smelling the disease: diagnostic potential of breath analysis. Mol Diagn Ther. 2023;27(3):321–347. doi:10.1007/s40291-023-00640-7

18. Hu J, Hu N, Pan D, et al. Smell cancer by machine learning-assisted peptide/MXene bioelectronic array. Biosens Bioelectron. 2024;262:116562. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2024.116562

19. Mathur M, Verma A, Singh A, Yadav BC, Chaudhary V. CuMoO4 nanorods-based acetone chemiresistor-enabled non-invasive breathomic-diagnosis of human diabetes and environmental monitoring. Environ Res. 2023;229:115931. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.115931

20. Chaudhary V, Talreja RK, Rustagi S, Walvekar R, Gautam A. High-performance H2 sensor based on Polyaniline-WO3 nanocomposite for portable batteries and breathomics-diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;52:1156–1163. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.08.151

21. Chaudhary V, Talreja RK, Khalid M, Rustagi S, Khosla A. Polypyrrole-Ag/AgCl nanocomposite-enabled exhaled breath-acetone monitoring non-invasive biosensor for diabetes diagnostics. ECS J Solid State Sci Technol. 2023;12(3):037003. doi:10.1149/2162-8777/acc2e4

22. Taha BA, Chaudhary V, Rustagi S, Singh P. Fate of sniff-the-diseases through nanomaterials-supported optical biochip sensors. ECS J Solid State Sci Technol. 2024;13(4):047004. doi:10.1149/2162-8777/ad3d0a

23. Hermawan A, Amrillah T, Riapanitra A, Ong W, Yin S. Prospects and challenges of mxenes as emerging sensing materials for flexible and wearable breath‐based biomarker diagnosis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(20). doi:10.1002/adhm.202100970

24. Ma P, Li J, Chen Y, et al. Non‐invasive exhaled breath diagnostic and monitoring technologies. Microw Opt Technol Lett. 2023;65(5):1475–1488. doi:10.1002/mop.33133

25. Chaudhary V, Taha BA, Lucky, et al. Nose-on-chip nanobiosensors for early detection of lung cancer breath biomarkers. ACS Sens. 2024. doi:10.1021/acssensors.4c01524

26. Xie X, Yu W, Wang L, et al. SERS-based AI diagnosis of lung and gastric cancer via exhaled breath. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2024;314:124181. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2024.124181

27. Mahdavi H, Rahbarpour S, Hosseini-Golgoo SM, Jamaati H. A single gas sensor assisted by machine learning algorithms for breath-based detection of COPD: a pilot study. Sens Actuators a Phys. 2024;376:115650. doi:10.1016/j.sna.2024.115650

28. Luo Y, Xu Z, He XL, et al. Electrical gas sensors based on metal–organic frameworks for breath diagnosis. Microchem J. 2024;199:109992. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2024.109992

29. Yang D, Gopal RA, Lkhagvaa T, Choi D. Metal-oxide gas sensors for exhaled-breath analysis: a review. Meas Sci Technol. 2021;32(10):102004. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ac03e3

30. Yang L, Zheng G, Cao Y, et al. Moisture-resistant, stretchable NOx gas sensors based on laser-induced graphene for environmental monitoring and breath analysis. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2022;8(1):78. doi:10.1038/s41378-022-00414-x

31. Chaudhary V, Khanna V, Ahmed Awan HT, et al. Towards hospital-on-chip supported by 2D MXenes-based 5th generation intelligent biosensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022:114847. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2022.114847

32. Chaudhary V, Sonu S, Taha BA, et al. Borophene-based nanomaterials: promising candidates for next-generation gas/vapor chemiresistors. J Mater Sci Technol. 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2024.08.038

33. Drera G, Freddi S, Emelianov AV, et al. Exploring the performance of a functionalized CNT-based sensor array for breathomics through clustering and classification algorithms: from gas sensing of selective biomarkers to discrimination of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. RSC Adv. 2021;11(48):30270–30282. doi:10.1039/D1RA03337A

34. Shanmugasundaram A, Munirathinam K, Lee DW. SnO2 nanostructure-based acetone sensors for breath analysis. Micro Nano Syst Lett. 2024;12(1):3. doi:10.1186/s40486-023-00196-5

35. Zhou X, Xue Z, Chen X, et al. Nanomaterial-based gas sensors used for breath diagnosis. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(16):3231–3248. doi:10.1039/C9TB02518A

36. Kim C, Kang MS, Raja IS, Oh JW, Joung YK, Han DW. Current issues and perspectives in nanosensors-based artificial olfactory systems for breath diagnostics and environmental exposure monitoring. TrAC Trends Analytical Chemistry. 2024;174:117656. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2024.117656

37. AL-Salman HNK, Hsu CY, Nizar Jawad Z, et al. Graphene oxide-based biosensors for detection of lung cancer: a review. Results Chem. 2024;7:101300. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2023.101300

38. Cardellicchio A, Lombardi A, Guaragnella C. Iterative complex network approach for chemical gas sensor array characterisation. The J Eng. 2019;2019(6):4612–4616. doi:10.1049/joe.2018.5125