With its ever-expanding capabilities, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not just a tool but a force shaping our future. It can write stories, replicate Rembrandt’s painting strokes, assist in adjudicating legal cases, aid medical treatment, recommend products, and even recognise human emotions. According to scientists, we are now in the third stage of AI evolution, a phase of deep learning and machine learning due to advancements in digital data and computing power. The third stage captures the transformation from a digital to a datafied society.

In a datafied society, data-based sense-making is central to constructing reality. This means systems processing data resembling intelligent behaviour are vital to our realities. UNESCO broadly defines the latter as the dynamic understanding of AI. The increasing influence of AI and machines in our lifeworld has sparked discussions on the emergence of digital habitus and human-machine interface implicating essential concerns like identities and democracy. These discussions have two main focuses: first, on how algorithms reshape our existence, and second, on the ethical implications of an algorithmic world on the human species. As we navigate this AI-driven future, staying engaged and thoughtful about its impact is crucial.

Pattern creation

AI and other technological innovations are technocratic Utopias created for a manageable present and predictable future. Interestingly, Jonathan Penn, a historian and philosopher of Science, highlighted how rule-following or conformity is the basis of pattern creation of behaviour and mind in AI. Furthermore, pattern identification is crucial for administrative and economic decisions and profit-making exercises. Patterns help in clear identification and engagement; thus, the legibility of human behaviour leads to social domination and control by the owners of technology. At the same time, randomness and unexpectedness of human lives and behaviour are unpredictable and do not follow patterns.

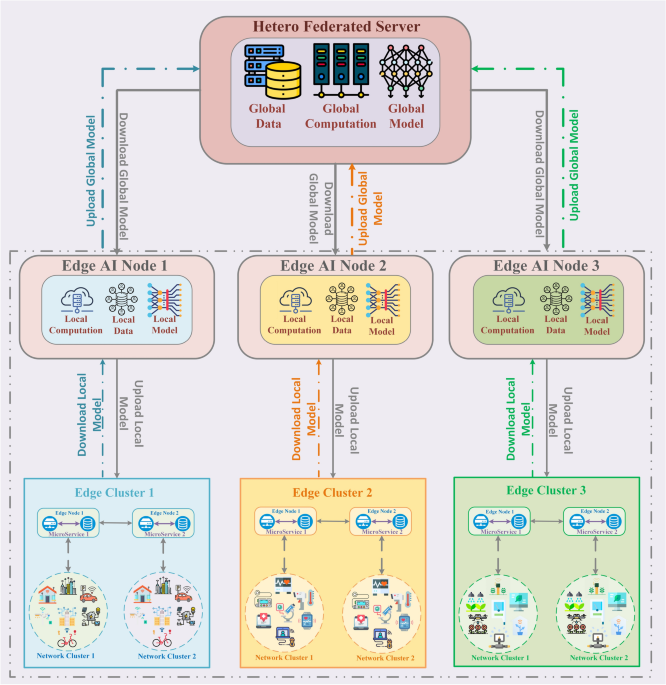

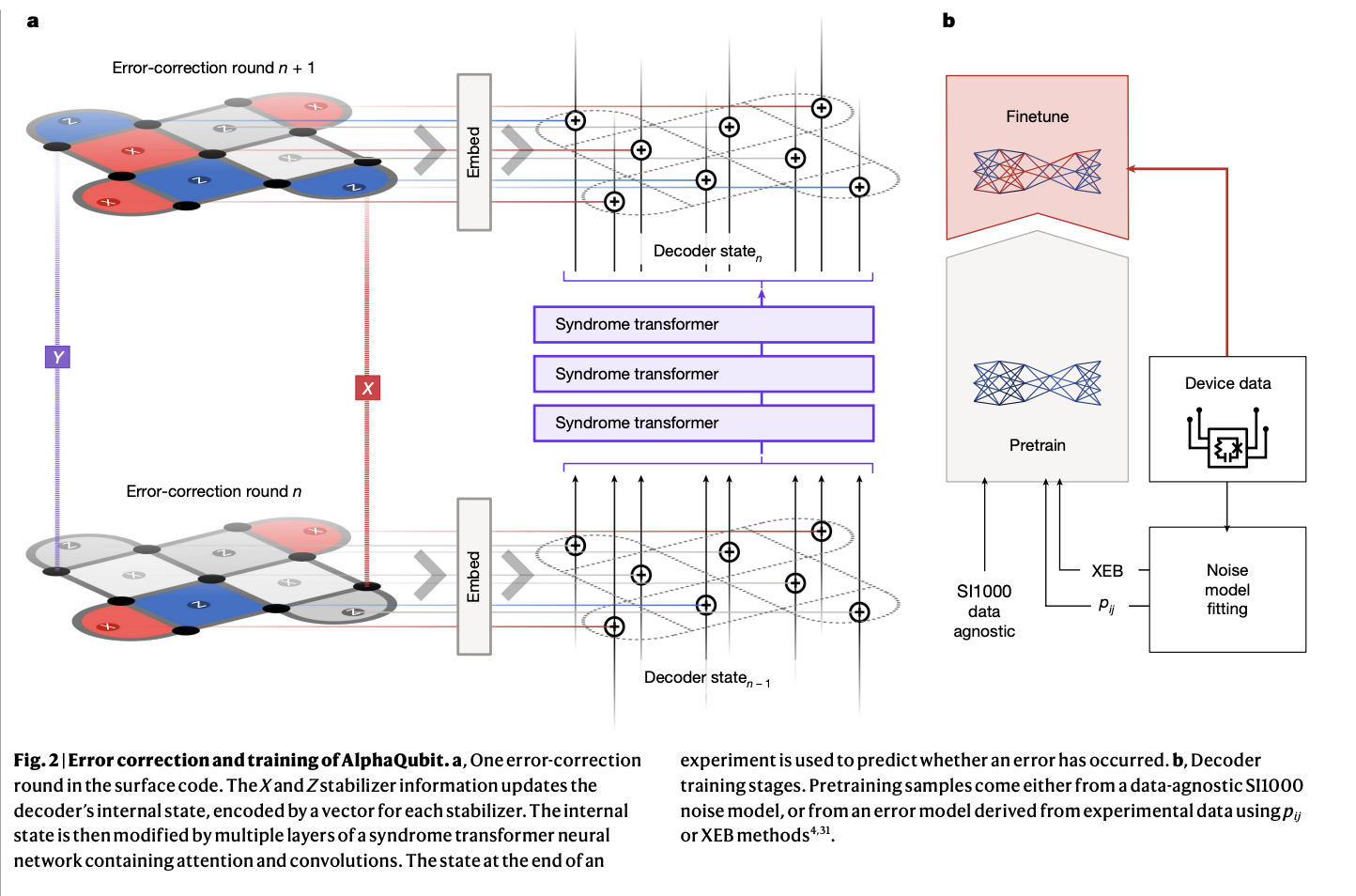

Machine learning aims at actionable predictions independent of human inputs. Formal mathematical models of human behaviour and intelligence is at the core of AI’s software and algorithms. These models represent a simplified version of the human mind and body that can be calculated and predicted. In essence, creating intelligent machines requires the formal encoding of patterns. The process of identifying and compiling these patterns is influenced by social factors, raising the question of who writes the code and what kind of representative sample is used to extract patterns that caricature the ‘human’ in machines.

User-centric AI

The cultural context and diverse meanings that arise from human interactions are standardised to a specific type. As a result, AI reflects and reproduces the social world of the algorithm developers. The biases and intentions of the algorithm creators underscore the politics of technology and raise ethical questions. Additionally, beyond the intention and language of the software, there are questions about who can access the data generated by the machines and how this data is used beyond the operation of a specific machine. These concerns underscore the importance of responsible AI and the development of user-centric AI, which ensures that data is not misused. Undoubtedly, these concerns lead us to the need for responsible AI and the design of user-centric AI, placing a guarantee for the non-misuse of data.

Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH), as fields of knowing the social world and ongoing conversation with human nature, play a critical role in forging responsible AI. A couple of years ago, an interdisciplinary platform in the U.K. brought together social scientists and philosophers to collaborate with data scientists, design specialists, policymakers, and industry to align the social power of AI with the moral and ethical values of human society.

SSH provides insights and enlightening historical perspectives on what happens when individuals in a society have reduced communitarian relations, implications of old and new inequalities, identification of incentives and disincentives (construction of ethical order of living) required to maintain social order, and most importantly, how new artefacts can impact the social and political power in a society. Automation technologies reorder the nature-human-machine relationship. However, to what extent should this recasting of relationship happen without displacing human dignity, privacy, accountability, transparency, and fairness? Responsible AI is, in short, a demand for a user-centric AI. SSH provides invaluable cues to these pertinent dimensions of technology-led social change.

The rise of machine agency raises the question of human creativity and innovation, especially for thinking beyond tools and software to fashion human lives. In the impending world of calculable human interactions and predictive behaviour, we must ponder on the role of randomness and contingencies in the human world. Technological breakthroughs, creative thinking, and engineering socio-political utopias do not follow predictable lines. Resistance to predications animates human agency by rescuing it from being one-dimensional and is the promise for humanity. To sustain these critical aspects of human lives, a continuous conversation with the social world and its creative expressions is needed more than before.

The writer is Assistant Professor of Sociology at GITAM University, Hyderabad.

Published – November 17, 2024 10:30 am IST